(Quick update to readers of HomeGrown Humans. We’re offering a super fun course for speakers and writers that shares a bunch of techniques to nail everything from a TED talk to a full length non-fiction book. We’ve had fantastic interest on our other channels, but wanted to share it hear, cuz you’re readers, and they tend to make the best writers! Check it here if upping your communication and storytelling game is in your tea leaves).

Onto the topic du jour…

A recent paper out of Argentina argues that in the quest for what put the sapiens in home sapiens, none other than our little magic mushroom friends are to blame.

The practice [of eating mushrooms] likely influenced the development of human cognition and awareness, according to a recent review examining psilocybin’s effect on human consciousness. Published in June 2024 by the Miguel Lillo Foundation, a research organization in Argentina, the review concludes that psilocybin not only influenced an individual’s perceptions while under its effects, but shaped human consciousness as a whole over the thousands of generations that humans had been eating psychedelic fungi.

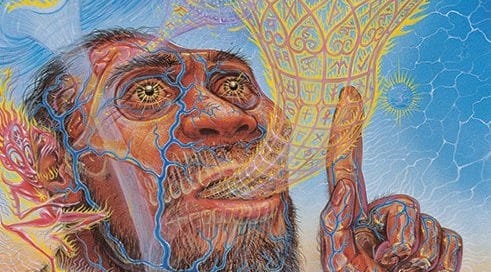

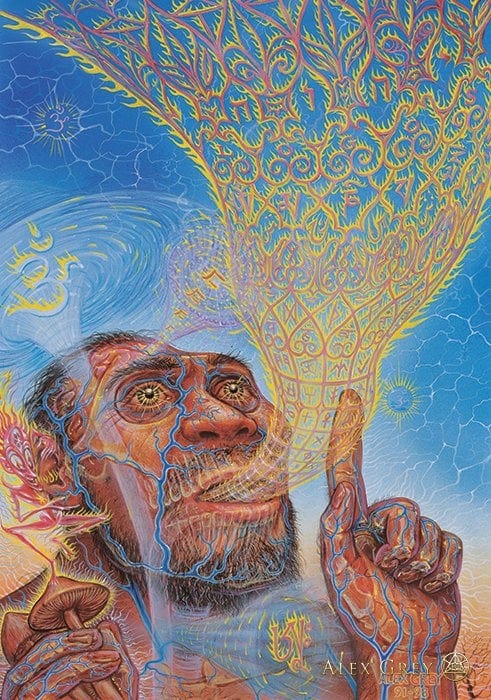

Painting by Alex Grey

The cognitive bump from the magical mushies “increases connectivity between networks in the frontal region and raises the level of awareness of states of consciousness,” says Fatima Calvo of the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, a biologist and co-author on the review paper.

The authors go on to state that micro-dosing hunter gatherers would’ve experienced keener eyesight, better hunting, and even heightened mating fitness. Which sounds an awful lot like Terrance McKenna’s infamous Stoned Ape theory of consciousness (which gets only a passing mention in the paper).

In the mid-1990s, McKenna, the infamous psychedelic philosopher and heir to Timothy Leary’s throne, took a wild swing at the origins of consciousness. He believed he’d found the answer to the central paradox of human existence—namely, how’d we get so damned smart all of a sudden?

According to McKenna, about one hundred million years ago our ancient African grandparents climbed down from the trees and began to explore the savanna. As they hunted and foraged for food they came across grazing animals like impala, gazelle, and wildebeest. Those massive herds left piles of dung behind them. The droppings hosted millions of insects that were an easy-to-harvest protein source, and well worth picking through to find.

The dung hosted another plentiful food supply—fungi. Among the best-known varieties that sprout on cow pies are Psilocybe cubensis, a.k.a. “magic mushrooms.” Entomologists speculate that these mushrooms first secreted psychedelic compounds as a natural insect repellent.

Tripping dung beetles, they theorized, often wandered off and forgot to finish eating the rest of the mushroom. Problem solved.

McKenna, though, saw a much grander role for those humble toadstools. He mused that complex linguistics sprang from the synaptic superconductivity of the psychedelic trip.

It was, according to McKenna, the most likely candidate for how we went from grunting and pointing to poetry and song. And the truly heroic, blow-out-the-pipes shamanic adventure—or, as he so memorably put it, “Five grams in silent darkness”? The catalyst for nothing less than the prehistoric birth of awe and the origins of religion.

Serious anthropologists never gave the Stoned Ape theory much credence.

Even sympathetic scholars found that McKenna was playing fast and loose with citations and ignoring counterfactual examples in the literature (like bloody Aztec mushroom sacrifices, violent ayahuascan Amazonian tribes, or sociopathic CIA programs).

But the theory never disappeared, either. If anything, it’s enjoying a recent resurgence along with all things psychedelic, as that new Argentinian paper illustrates.

We might not have to stretch as far as McKenna’s ramblings, though, to find what distinguishes us from our nearest primate cousins.

To refine our search for the causes of consciousness we need to ask what else could have provided the neurological boost to transform us from the ape who stands (Homo erectus) to the ape who knows (Homo sapiens)?

A plausible alternate candidate to the Stoned Ape hypothesis would have to check three boxes:

It would need to be strongly instinctive, feel powerfully rewarding, and enjoy widespread adoption.

It would have to meaningfully shift physiology and psychology, and be able to do so repeatedly over time.

In sum, the transformative substance or practice would need to be what psychologists call autotelic—meaning it would have to have its own intrinsic reason and reward for doing.

It might not have been the Stoned Ape that tripped us awake, but it could have been his far more widespread cousin, the Horned Ape, the ape who differs from all his primate relatives in the way he engages love and sex.

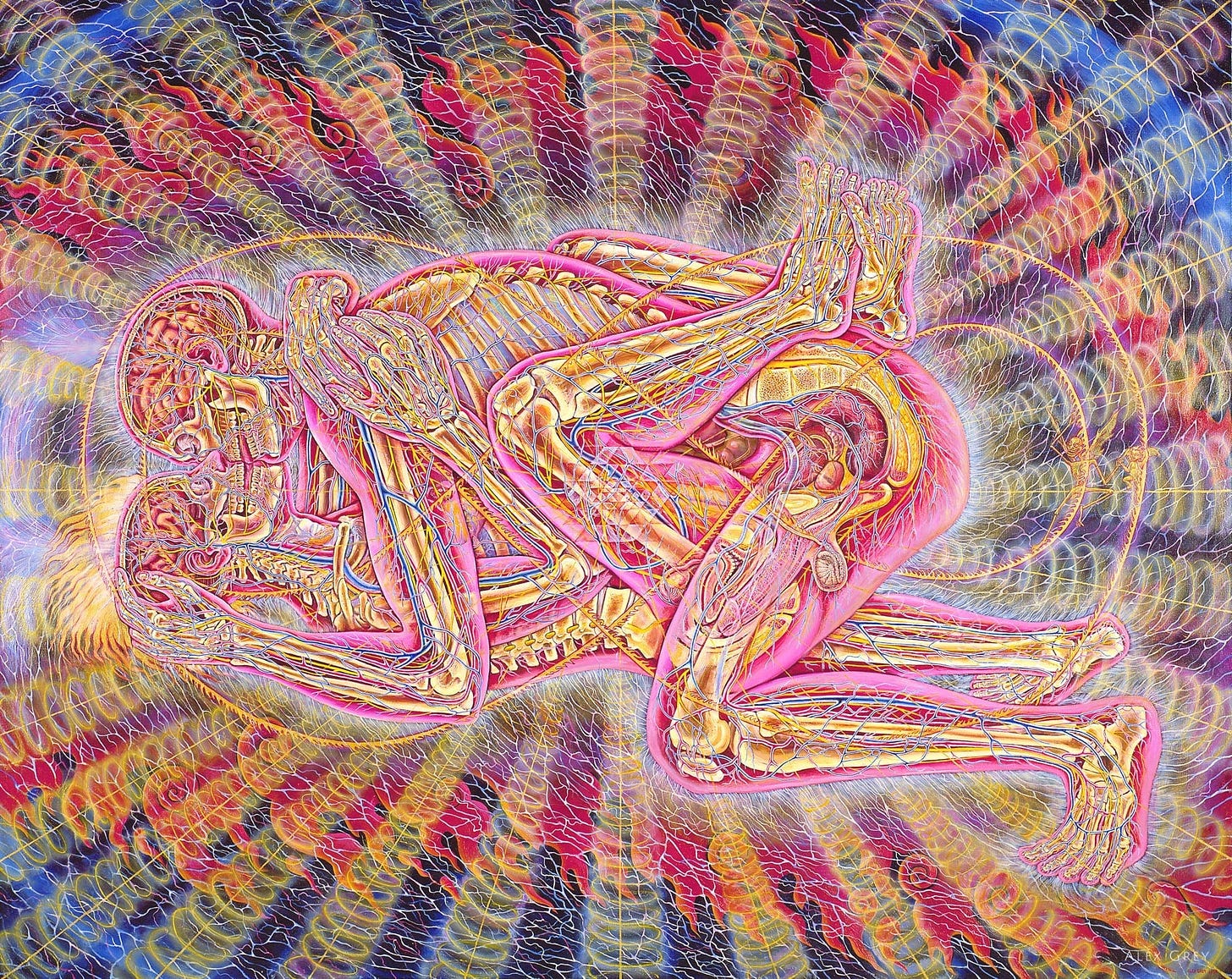

Painting by Alex Grey

The Horned Ape is a more plausible missing link between Homo erectus and Homo sapiens. Or, to give him his proper Latin name, Homo coitus—the ape who gets it on.

Jared Diamond, the Pulitzer Prize–winning UCLA anthropologist, makes exactly this case. In Why Is Sex Fun?: The Evolution of Hu man Sexuality, he compares us to different primate and animal species and comes to a controversial conclusion:

Growing bigger brains didn’t create our sexual habits, as Freud would have insisted. Instead, our sexual habits created our bigger brains.

If true, this upends everything we’ve assumed about how human consciousness and culture developed.

“While paleontologists usually attribute the evolution of [culture, speech, and complex tools] to our attainment of large brains and upright postures,” Diamond argues, “our bizarre sexuality was equally essential for their evolution.”

Concealed fertility, abundant recreational sex, permanent female breasts, frequent female orgasm, and larger penises occur nowhere else in the animal kingdom. We are so different, in fact, that any accounting of our rapid acceleration into Homo sapiens has to consider our divergent sexuality as a prime candidate fueling that change.

“Within the relatively short period during which our ancestors and the ancestors of our great ape relatives have been evolving separately,” Diamond explains, “along with posture and brain size, sexuality completes the trinity of the decisive respects in which the ancestors of humans and great apes diverged. . . . Recreational sex . . . was as important for our development of fire, language, art, and writing as were our upright posture and large brains” [emphasis added].

And the reward circuitry that incites romance encouraged us to go back to those waters, again and again.

Over time, those altered, more expansive and connected experiences became a permanent part of our thinking and being.

Norepinephrine energizing us and sharpening our focus.

Dopamine rewarding our explorations and new discoveries.

Endorphins and anandamide easing our aches and providing brief relief from the grind of life.

Oxytocin bonding us to our lovers and offspring.

Slower brain waves allowing subconscious thinking and inspiration.

Our altered states became altered traits, one orgasm at a time.

***

So Stoned Ape or Horned Ape? Terence McKenna argued that our ancestors must have eaten magic mushrooms to wake ourselves up.

But that’s a tenuous theory, impossible to prove from here. Based on the anthropological record, the Horned Ape—the primate that sexed itself into higher consciousness—seems a more likely candidate.

If we agree with Diamond and other anthropologists who argue that sexuality accelerated human consciousness and culture, we also have to reckon with all of the pain and suffering that those unconscious drives continue to cause.

Sure, we can bowl strikes all day long, aiming precisely for the romantic path we desire. But on either side of that narrow path, gravity and biology beckon. A lapse in attention, or a slip of the wrist, and the gutter ball waits for us all.

That realization offers us a shot at redemption. We can transform the suffering and confusion that our sexuality has often caused.

All of that imprinting, all of that relentless drive to procreate can be repurposed.

Rather than dancing like puppets on the strings of indifferent evolution, we can untie those strings and begin to stand on our own two feet.

We can hot-wire evolution.

(and no one needs to wait for Phase III clinical trials to get cracking)

I'd like to posit a third, integral theory: the Stoned AND horny ape... fucking while high on mushrooms? Most highly plausible :)

I'm most curious about your conclusion and what is meant.

"Rather than dancing like puppets on the strings of indifferent evolution, we can untie those strings and begin to stand on our own two feet.

We can hot-wire evolution."

This reminds me of Richard Dawkins' concept of a meme in evolution. Looking forward to a future post!