Psychology is Dead

Why It's Long Past Time for an Update

Ed Note: last few hours to book one of the interview spots for our upcoming course Human 2.0. It’s a dive into the physiology, psychology and epistemology of living large in the 21st century. This following essay is an intro to some of the frames we’ll be exploring in more detail starting next week. If it’s of interest, check it out.

***

We’re in a tight spot.

And it doesn’t really matter what’s in your newsfeed lately.

Could be civil unrest and the rise of authoritarianism.

Or the smashing of planetary boundaries, forest fires and ocean garbage patches.

Or your whipsawing 401K and scary layoff statistics at the biggest tech companies.

Or your disengaged college kid using AI to write papers for a career that might not even exist by the time they graduate (but the student loans will)

A decade ago, the psychiatric community added “general adjustment disorder” to its lexicon of illnesses in the DSM V.

It meant that a given patient was really having a tough time with, you know, all of it.

Back in those simpler times, therapists encouraged those kinds of patients to engage in a little Stoic-lite Cognitive Behavioral Therapy.

(which lies somewhere between “are you sure you’re sure?” and “suck it up, fat kid!”)

The premise back then, was that someone who was worried sick about some thread of the polycrisis was basically hyperventilating about things that they couldn’t possibly know were that bad, or that determined.

And besides, isn’t this really about your last breakup and how that made you think of your mother abandoning the family when you were in middle school?

The polar bears and redwoods (or street protests and hate crimes) are just placeholders for your true anxieties–which are all personal and solvable!

Or at the very least prescribable and reimbursable.

#latestageglobocapFTW

But we never really recovered from Covid, lockdowns and the rupturing of consensus reality that came with it.

So folks are diving into Christianity.

And ketamine.

AI psychosis

And “mass formation psychosis” (if you’re feeling a bit more social).

Really, anything we can get our hands on to soothe us or save us. To lend meaning and structure to a world that’s gone all gooey under our feet.

So yes, no doubt, shit’s getting weird.

But also…

We’re not built for this shit, either.

At all.

Part of the problem is that we’re running deeply outdated maps and models as to who we are, and how we function.

So when we dis-function, we’ve got no idea how to fix it all.

At this point, we’ve all heard Harvard biologist E.O. Wilson’s chestnut about “possessing paleolithic brains, medieval institutions and god-like technologies.”

But at a simpler and far more recent level, we have Freudian psychologies. And they’re simply no longer fit for purpose.

Current findings from neuroscience, AI computing and physics suggest that 20th century models of individual selfhood and identity are crude approximations for who (and how) we really are.

The current mental health crisis highlights this glaring mismatch. Our isolation as lonely neurotic, medicated individuals is killing us. And it’s long past time for an update.

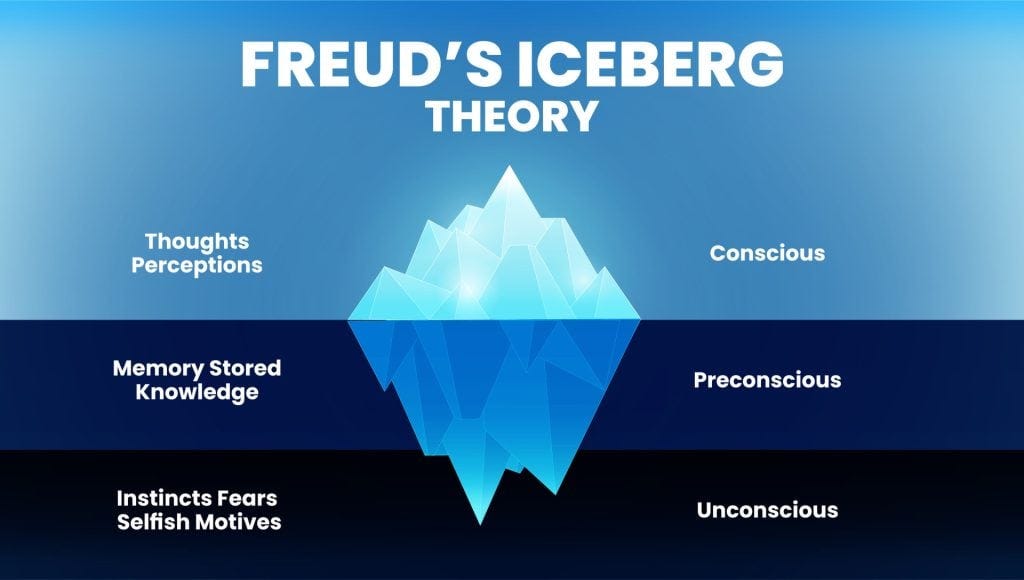

Starting with Freud’s foundational model of psychology, we learned to think of ourselves as icebergs. The “conscious self” poked its head above water, while the dark “unconscious” lurked below the waterline.

The goal of becoming a well-adjusted grownup was to bring as much of that repressed material from the unconscious to the conscious, via plenty of couch time with an analyst.

Despite falling out of favor with most psychologists, that Freudian model still serves as our default of who we think we really are–our conscious selves trying to manage and master our unconscious impulses by dragging them above the waterline of self-awareness.

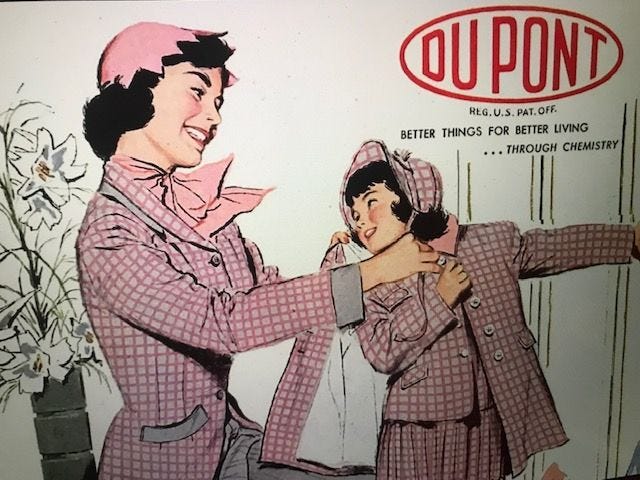

From the 1990’s onward, a more neuro-chemical understanding took charge.

We shifted our attention from analyzing dreams about our mothers to titrating serotonin in our brains.

Depression, anxiety, inattention and insomnia, were all “curable” by tweaking our prescriptions. Talking about our feelings was out, better living through chemistry was in.

Despite spending billions of dollars on both approaches, neither the Freudian model of self-analysis, nor the pharmacological model of mental illness have held up very well.

In the wake of their collapse, we haven’t really built anything more current or coherent.

A wave of recent research into consciousness, psychology and artificial intelligence, ranging from neuroscientists like Robert Sapolsky’s critique of Free Will which insists all of our actions and simply turtles-all-the-way-down reactions to prior inputs, to Lisa Feldman Barrett’s theory of Constructed Emotion which argues that we make up our emotions after the fact to justify our gut-level “interoception”, is radically revising our notions of what makes us tick and what it means to be human.

Rather than our unconscious selves simply being repressed versions of our conscious selves, Feldman Barrett, David Eagleman and others would reframe it much more along the lines that our conscious self isn’t the rider–the one in control and sitting on top of the more primal self. Instead, in these more current findings, our conscious self is “like the headlines on the Sunday edition of the New York Times.” Late to the party, summarizing a ton of more interesting information and stories, and a fraction of what’s contained within.

These days it’s less about rendering the unconscious conscious, or tweaking our neurochemistry to tune our moods than it is about understanding selfhood as a dynamic and counterintuitive system.

Pull on any thread of our self identity and the whole sense of what Alan Watts called our “skin encapsulated egos’‘ breaks down in light of this new research.

While at first this might seem disorienting, we clearly need to broaden our psychological horizons. Our isolated neurotic selves can’t handle the stresses and uncertainties of what’s happening right now, let alone what’s likely to come.

If you think about it, it’s not just Freud’s iceberg that’s sunk us.

It’s all of the metaphors or assumptions that govern our working models of who we are.

A few examples:

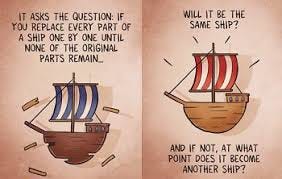

Like Theseus’ Ship, we’re forever replacing our cells. Some, like the ones in our gut, swap out as rapidly as weekly. Others, like in our skeleton, only once a decade. A few, like our eye lenses and heart stay with us for the long haul.

But when you think of yourself at age ten or twenty, with the knowledge that nearly every plank in your boat has been swapped out for a new one, how much continuity do we really have with our former selves? Are we even the same people?

Well, you might reasonably argue, “I am the sum total of my lived experiences. The story of me, held in my memories, are what is essentially me.”

Except neuroscientists and psychologists have both revealed exactly how plastic and unreliable our memories really are!

Whether it’s the famous studies of “flashbulb moments” like JFK’s assassination, the Challenger explosion, or the fall of the Twin Towers, folks interviewed that same week, and then followed up with at regular intervals years later turn out to constantly reinvent who they were with, where they first heard the news, and how it felt.

Or take an example closer to home for many of us–a blissfully staged wedding photo that gets re-written after that lying snake in the grass got outed as the cheat they always were!

Our memories are plastic, elastic and fundamentally untrustworthy. (that’s also the central mechanism that PTSD therapies rely on, BTW—reworking traumatic memories and rendering them more liveable over time)

So if we’re not our repressed unconscious as Freud insisted, and we’re not simply our neurochemistry as Prozac nation convinced us, and we’re not our self-replacing bodies, and we can’t even trust our memories…

Then who in the hell are we?

By expanding our sense of who we are, across time and across generations and perspectives, we gain more resilience and can handle larger amounts of suffering without breaking.

As Stanford professor Iris Schrijver writes in Living with the Stars: How the Human Body is Connected to the Life Cycles of the Earth, the Planets and the Stars,

“Everything we are and everything in the universe and on Earth originated from stardust and it continues to float through us even today. We’re not fixed at all. We’re more like a pattern or a process…exploring our interconnectedness with the universe.”

So instead of living above our necks, inside the whirring hamster wheels of our tiny little minds, we might exhale a bit.

Understand that we are, as stoney Carl Sagan reminded us, just stardust, man.

But also that we are constantly shifting and changing, “more a pattern or a process” as Schrijver suggests.

And that procession of us, includes our ancestors, as surely as it will one day include our descendants.

That there’s more to us than our fleeting neuroses and grievances. More than the sum of our trendy attachment style or rehashed trauma.

More even, than our current anxieties about our collective predicament.

Not because the threats aren’t real and present.

But because the Story of How We Begin to Remember, who we are, why we’re here, and what’s ours to do–is a narrative that requires us to step beyond our little stories of pain and pleasure and step into a bigger story of purpose.

Constantly.

When we find answers to those questions that ring true, they weave us into a larger tapestry.

We are a pattern. We are a process. We are more than the sum of our scrapbook memories and inner monologues.

For the briefest moment in time, for these fleeting lives of ours, we bear witness to this whole unfolding tragicomedy across the ages. And if we’re lucky we get to add a few verses that might even thicken the plot.

We are living on behalf of those that came before and those yet to be. The simple act of persisting and witnessing forge a linkage between past and future that only we can make.

It might not all work out for us in our lifetimes (no matter how much therapy or medications our old theories would suggest we need). But if we keep the faith that one day, it works out, our suffering is both contextualized as one link in a much longer chain, and valorized as essential to the final outcome.

We can keep on keeping on because everyone before us and after us is banking on us.

As the late great Vegas Elvis once sang, a little less conversation, and little more action

A little less conversation, a little more action please

All this aggravation ain't satisfactionin' me

A little more bite and a little less bark

A little less fight and a little more spark

Close your mouth and open up your heart and baby satisfy me

Satisfy me!

Some key concepts in here, and ideas to revisit. "We are a pattern. We are a process." The ship of Theseus plus the hallucinated/tweaked memories is a noteworthy combo. Then what are we? And how does this inform how we live, work, play, and relate to each other? I appreciate this inquiry. Thank you Jamie.

Beautiful! I feel better now. Though I'd like to see the Elvis video! (I'll look it up.) One wondering: Does keeping the faith necessarily include believing that it will for sure all work out?