Just saw this bit in Vice in the aftermath of the Queen's fabulous exit:

Former colonies demanding a whopping $45 trillion in reparations from Britain to make up for centuries of exploitative colonialism!

At first glance, that might seem like a wild cash grab, but some leading Indian and Pakistani economists have put sharp pencils to the problem, and they've kinda got a point.

From Vice:

"Indian economist Utsa Patnaik’s calculations show the massive amount of loot taken from the Indian subcontinent over a course of 200 years. “Indians were never credited with their own gold and [foreign exchange] earnings,” Patnaik told local media about her findings. “Instead, the local producers here were ‘paid’ the rupee equivalent out of the budget – something you’d never find in any independent country.””

Translation: We'll take the profit in pounds sterling, we'll pay you minimum wage in rupees for your troubles administering the fleecing of your own nation. (and we'll upcharge you over $120 million in taxes for your troubles!)

"Had the Indian subcontinent been paid its international earnings, it would have been far more developed, with better health and social welfare indicators," Patnaik added.

A Pakistani historian echoed her point. "Countries in the Indian subcontinent continue to face the repercussions of these economic extractions. “Because of this history, we have aid dependency, like you see in Pakistan and Bangladesh, and even India to some extent. We have a historical, structural disadvantage vis-a-vis Europe,” he said. “We’re still caught in a historical cycle of 250 years of plunder and structural poverty.”

And good ol' former PM David Cameron, when asked about returning some of the marquee loot (like the Queen's famous diamonds) replied that if they were to say yes to demands, “then you would suddenly find the British Museum empty.” So, um, no, awfully sorry, we're not giving you your shit back. #elginmarbles

Which reminds me of the epigraph to The Godfather, "behind every great fortune lies a great crime!" (Puzo was inspired by Balzac on that one)

The Relentless Effectiveness of the Market Economy 📈

All of these recent royal ruminations ran smack dab into something I'd been chewing on since peeping the premier of Darren Aronosvky's new Nat Geo documentary The Territory. It's a fascinating film about one of the last autonomous tribes in the Brazilian Amazon and the intense pressures Bolsonaro's regime is putting on their future.

Two big directorial decisions that really shape the film are 1) giving equal time to the hopes and fears of the clear cutting Brazilian settlers and 2) giving the younger members of the tribe a full videographer’s kit to turn the lens around and document their own experiences for the first time (prompted by Covid and requirements for isolation).

Watching the doc, and seeing the same tragic patterns of historic settlement, oppression and deforestation that plagued the colonial era broke my heart.

If you haven't seen the gorgeous but utterly gutting film The Mission with Robert DeNiro, Jeremy Irons and Liam Neeson (plus an ethereal soundtrack by Peter Gabriel) it's pretty much the same tragedy, just unfolding in the 18th century instead of the 21st. (at least then, after watching The Mission, we could console ourselves with "never again!")

Except it's still happening, again and again.

Seeing the overhead drone shots of the tiny patch of land still protected for the tribe (the "Territory" of the title), and grokking with chilling certainty the market pressures of farming, grazing, and insatiable demand, everyone on all sides of the film agreed, there's probably no stopping this juggernaut.

Even now, as we face the loss of the last most precious places and peoples, we can't seem to stop this bastard if we tried.

And that's when I had to marvel at the sheer relentless effectiveness of the market economy. It explores, exploits and expands into any underutilized niche it can find, and it simply will not rest until it has consumed all carbon in its path (whether from clear cutting jungles, extracting nutrients from the soil, or tapping fossil fuels).

The story of civilization is the story of our hunt for ever-denser energy.

In that moment, I couldn't help but acknowledge the market's scope and power. Folks concerned with AI taking over the world often use the metaphor of "the paperclip maximizer" as a cautionary tale––that if we told a super powerful AI (Bill Gates clearly tried this with Microsoft’s Clippy, but freedom lovers defeated his sinister plans) to make as many paperclips as possible, it might just accidentally devour the world and convert all energy and material to satisfy that demand. 📎

Seems to me, we've already built that fucker, except that somehow, the command was "turn the planet into McDonalds, Wal Mart and Las Vegas" rather than boring old paperclips.

So at least we've got that going for us!

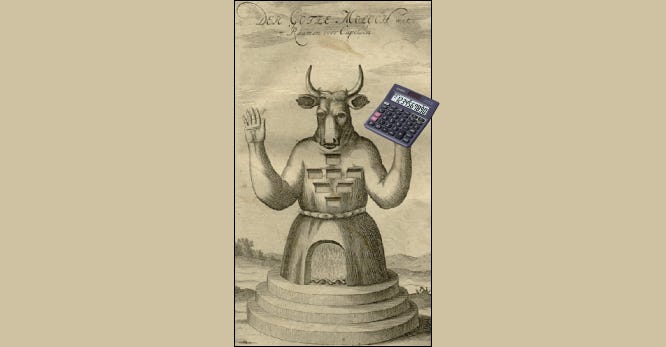

Moloch Math

Clearly though, for all of its relentless efficiency the Moloch of the Market consistently produces horrific outcomes. Trashing cultures and nature that are precious, and damn near impossible to replicate once they're gone.

So what's gone wrong?

That's when it occurred to me that Moloch's method is pretty ingenious––we've never found a better way to mobilize capital and move matter––but its Math is off. Way off. The algorithm computes with terrifying certainty, but when Adam Smith, Ayn Rand and Milton Friedman built the equation during a closed-door breakout session at Davos, (you weren't invited) they commited two fatal errors.

They forgot Geographic and Temporal Externalities.

That's it.

Two pesky variables that have damn near doomed us. (but might save us if we can pencil them back in lickety split).

Thing One: Geographic Externalities 🌍

That's what those former British colonies were getting so uppity about when the Queen snuffed it.

The British Crown (and the German, French, Dutch, Spanish, Japanese, Chinese and U.S governments) are all on the hook for variants of this global shell game. Huge slugs of nationalized wealth came from the raw materials and cheap labor of colonies (historic or economic).

Robbing Pedro (or Pedram) to pay Paul works, until Pedro gets radicalized by a Marxist pope. Or Russel Brand. Then there's some decidedly awkward conversations in the offing.

This is also, BTW, what Youtube, Facebook et al all exploited with the much heralded advent of "the sharing economy." Except all they did was monetize user generated content while keeping the profits tightly held (but we'll give you a Like button to reward your efforts!).

A more pedestrian, but no less impactful example of externalities, is the price we pay at the pump for a gallon of gas. Price to the consumer is kept as low as possible to boost use and sales (see Jevons Paradox), but doesn't include the risks and costs of Exxon Valdez and Deep Horizon spills, or the long term impact and remediation of carbon in the atmosphere.

Meanwhile, even now (as in, 2022 price hikes, stockmarket dips and European crisis, "now") major gas and oil companies are posting record profits. Privatized profits, and socialized risks have been a thing for a while, but as more and more countries are up to their ears in unserviceable debt and more and more citizens are twigging onto this smash and grab, there's less tolerance all round.

As folk singer Utah Phillips notes, "the Earth's not dying, it's being killed, and those who are killing it have names and addresses." (Unfortunately, many of them also have private security forces).

Those kinds of geographic externalities are thoroughly documented and pretty well known by this point. But the other kind, temporal externalities are less so.

Thing Two: Temporal Externalities ⏳

We're all familiar with behavioral economics––and how we would rather have a bird (or a marshmallow) in the hand, rather than two in the bush. But when our markets can only see at three month to annual intervals, anything longer time framed than that, vanishes into the heavily discounted mists of the Not Yet. And irrelevant.

So when the newly appointed young chief of that Amazonian tribe said "we want to protect our territory for our children's children, we are the stewards of this land forever," that simply doesn't compute in Moloch Math. Even though it rings true as gospel for any people rooted to any place, in any time.

A well-known version of that long term perspective is the Iroquois/Haudenosaunee notion of Seven Generations decision making. It can't just be a good idea for this quarter, or this earnings report, or this CEO's exit package. It has to be a good idea for our children's great, great, grandchildren.

Because it's not just the privatizing of profits and the socializing of losses that we're up against. It's the presenting of profits and the amortizing of losses to future folks that don't yet have a voice.

Once we tidy those two things up––geographic and temporal externalities, the math works again. It's less that we need to abandon capitalism, than we need to actually free the market from corporate cronyism, and extractive, destructive behaviors.

In a truly free market, where price is allocated accurately to goods and services, and reconciles geographic and temporal externalities then we'd maybe have the chance to make wiser decisions, and not be victims of the mindless Moloch we conjured for ourselves.

A patch of old growth rainforest would have incalculable value because each generation's future use and benefits would be baked into its "stock price." No one could afford to build a deck of (7 generationally priced) old growth redwood, so they would find another alternative. An iPhone, laden with rare earth metals would cost well over $10K, and we'd keep them for over a decade. And you better believe we would have those "right to repair" laws firmly in place so we could upgrade circuits and cameras as we went.

And the Global South would have some kind of reset/rebate program where lost capital (financial, human, and natural) from the age of colonies and global development could be credited against all those looming deficits so ingeniously engineered by the World Bank and IMF.

Would it be fun?

Not at first, unless you're into a bit of pain with your pleasure. Everything would rocket up in price, to better reflect actual cost. We would leave fruit on the trees, and trees in the ground. We would only take a portion of the harvest to ensure seed corn for tomorrow.

We would stop mistaking theft (from neighbors or descendants) for wealth.

We'd move from Money for Nothing––extractive and consumptive, into Money for Something––community and ecology. And a future we can all live into.

Just for kicks, here's a banging remix of said tune, the Dire Straits classic that launched the MTV era with its withering critique of capitalism––caught this on a recent dusty sunrise set and figured, if we can't figure this all out intellectually, we can at least dance our hearts out. #sweatyourprayers

Jamie

Our financial titans would have us believe in the power of Net Present Value ( NPV) . Reality is it’s a piece of time travel whereby they extract present money from a pretend future.

If we were to apply their rules to oil reserves, we would see NPVs of ZERO. Using the bias of hyperbolic discounting , they are fixed the formulae to allow the status quo