We might not say it in mixed company, but after 9/11, Katrina, the pandemic, Ukraine, Gaza and Hurricane Helene we’ve all been thinking a lot more about the unthinkable.

Newfeeds just this week have shown us rockets raining down on Israel and a hurricane raining down on the Carolinas and Katmandu.

But this week is less of an aberration, than it is a relentless progression. We’re all become increasingly aware of the tenuousness of our civilizational norms.

And wondering what the hell we do about it.

As far back as 2012, National Geographic launched a reality show called Doomsday Preppers about people getting ready for a time described in casually terrifying acronyms like WROL (without rule of law) WTSHTF (when the shit hits the fan) during the EOTWAWKI (End of the World as We Know It).

Its first episode racked up over four million viewers (nearly half a million more viewers than the top late-night comedy show pulls in).

Doomsday Preppers has gone on to break records for the channel and become one of its top ranked shows. Baffled by their own success, National Geographic put out a survey to learn more about their breakout hit. It revealed that nearly half of Americans think that investing in bomb shelters and MREs (nonperishable military rations) is a safer bet than socking their savings away in a 401(k).

The American dream of white picket fences, 2.2 happy children, and pension funds is getting eclipsed by visions of fortified bunkers, gold bullion, and bug-out bags.

We like to believe that we’ll all pull together in times of crisis. We put our faith in governments, national guards, firefighters, policemen, and institutions like the Red Cross.

In 2019, Brock Long, the administrator of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) during Houston’s and Puerto Rico’s historic flooding, offered a reality check on disaster relief as a service:

“I think FEMA faces unrealistic expectations by Congress and the American public,” he said. “We’ve got to stop looking at FEMA as 911.”

Take the recent collapse in insurance markets in Florida and California, where home sellers are now offering no-fault outs for buyers who can’t find affordable insurance, and you realize we’re on the cusp of the failure of the entire mortgage and real estate asset bubble.

“I think, to some degree, we all collectively take it on faith that our country works,” Steve Huffman, the CEO of the popular online message board Reddit, reflects. “All of these things that we hold dear work because we believe they work. While I do believe they’re quite resilient, and we’ve been through a lot, certainly we’re going to go through a lot more.”

Our desire to believe it will all work out somehow lies somewhere between wishful thinking and learned helplessness. “What experience and history teach us is this,” the German philosopher Georg Hegel warned, “peoples and governments have never learned anything from history.”

***

But those with the biggest bets to place are hedging them madly.

Back in 2017 (in those happy BeforeTimes we barely remember now), Evan Osnos published “Doomsday Prep for the Super Rich” in The New Yorker, detailing exactly what those with the information and resources to plan ahead are up to.

The article caused an immediate sensation and spawned over half a million responses online.

“Survivalism, the practice of preparing for a crackup of civilization,” Osnos admits in his introduction, “tends to evoke a certain picture: the woodsman in the tinfoil hat, the hysteric with the hoard of beans, the religious doomsayer. But in recent years survivalism has expanded to more affluent quarters, taking root in Silicon Valley and New York City, among technology executives, hedge-fund managers, and others in their economic cohort.”

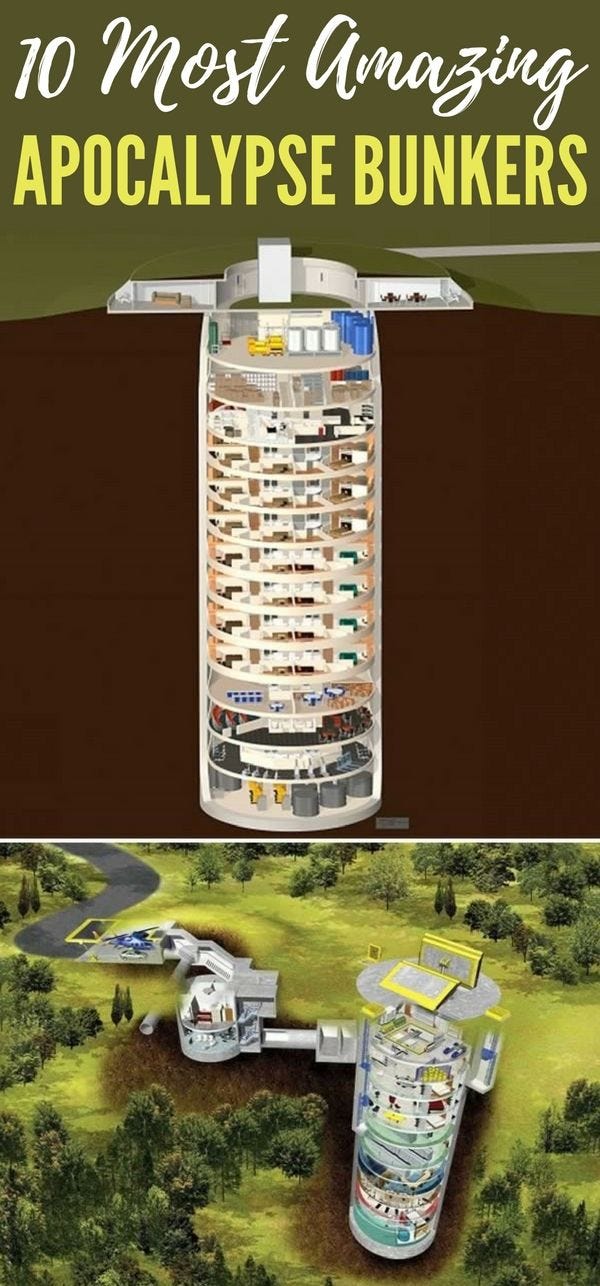

When Osnos interviewed LinkedIn founder Reid Hoffman about how widespread this contingency planning was among tech elites, he estimated “fifty-plus percent.” “Saying you’re ‘buying a house in New Zealand’ is kind of a wink, wink, say no more,” he continued. “Once you’ve done the Masonic handshake, they’ll be, like, ‘Oh, you know, I have a broker who sells old ICBM silos, and they’re nuclear-hardened, and they kind of look like they would be interesting to live in.’”

As the success of National Geographic’s Doomsday Preppers confirms, we’re all interested in having a backup for when the S.H.T.F. Some of us just have more bullion and better bunkers.

A couple of summers ago, author Douglas Rushkoff (Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus), named one of the “world’s most influential intellectuals” by MIT, wrote what amounted to an update to Evan Osnos’s New Yorker essay.

And in a couple of years, we’d moved from the hypothetical to the nearly unthinkable.

Rushkoff received an invitation to address a bunch of Wall Street financiers on the future of technology—a topic that he had spent his career tracking.

And while he usually turned down those kinds of cushy speaking engagements (he was a founder of the cyberpunk movement back in the ’90s, after all), he admitted that “it was by far the largest fee I had ever been offered for a talk—about half my annual professor’s salary.” So he swallowed his disdain and did what most reasonable people would: He took the gig.

He showed up on the appointed day in what he assumed was the greenroom (the place backstage where speakers and hosts usually congregate during conferences). Five impeccably dressed men sat down and introduced themselves. Slowly Rushkoff realized this wasn’t the green room and there was no stage.

There was no auditorium full of traders waiting to hear him talk either. These five men were his audience.

At first, they asked him a few easy icebreaker questions—what was the deal with blockchain and cryptocurrencies? How far off did he think quantum computing was? Can Google really upload Ray Kurzweil’s mind to the cloud? Alaska or New Zealand (to escape global warming)?

But then came the real question—the one those five titans of Wall Street had paid north of $50,000 an hour to learn: “How do I maintain authority over my security force after the event?”

That sentence requires some unpacking.

Let’s start at the end and work backward.

“The Event.”

“That was their euphemism,” Rushkoff explains, “for the environmental collapse, social unrest, nuclear explosion, unstoppable virus, or Mr. Robot hack that takes everything down.”

By this point, discussing, debating, or wondering about future scenarios had given way for these men to a chillingly simple placeholder. Simply, The Event. And while these men may not have been willing to bet on which particular domino would fall first, that they all would topple soon after seemed self-evident. A fixed constant in a more complex equation they were still trying to solve.

Next, the verb.

“Maintain authority”—carries the distinct implication that

a) authority might be challenged or questioned in the near future and

b) that those five men had it and intended to hold on to it.

Finally the object of that action, the noun.

“My security force.” Not “my personal assistant.” Not “my body man,” “butler,” or “team.”

My “security force.” Unvarnished. Plural, even without an s. And judging by the urgency of their $64,000 question on how to control that group after The Event, possibly mercenary.

For the remainder of their allotted hour together, those hedge fund managers laid down a few more of their cards.

How would they pay their paramilitary if the economic system collapsed and paper (and digital currency) became worthless?

How would they prevent a Lord of the Flies–style coup once things went pear-shaped?

Would secret combination locks on food supplies work?

How about shock collars?

Or AI robots?

“That’s when it hit me,” Rushkoff said. “At least as far as these gentlemen were concerned, this was a talk about the future of technology.

Taking their cue from Elon Musk colonizing Mars, Sam Altman gunning for omniscient AI, Peter Thiel reversing the aging process, or Ray Kurzweil uploading [his] mind into a supercomputer, they were preparing for a digital future that had a whole lot less to do with making the world a better place than it did with transcending the human condition altogether and insulating themselves from a very real and present danger of climate change, rising sea levels, mass migrations, global pandemics, nativist panic, and resource depletion.

For them, the future of technology is really about just one thing: escape.”

To his credit, Rushkoff challenged their assumptions. In response to their blunt questions he answered that the best way to maintain the loyalty of their private security forces was to start treating them really well, like family, starting now.

And to not stop there.

He suggested they do the same in all of their current businesses on this side of The Event. The more effectively they could do that, he suggested, the greater the odds we could all keep the wheels on civilization in the first place.

“They were amused by my optimism, but they didn’t really buy it,” Rushkoff admits.

“They were not interested in how to avoid a calamity; they’re convinced we are too far gone. For all their wealth and power, they don’t believe they can affect the future. They are simply accepting the darkest of all scenarios and then bringing whatever money and technology they can employ to insulate themselves—especially if they can’t get a seat on the rocket to Mars . . . the result will be less a continuation of the human diaspora than a lifeboat for the elite.”

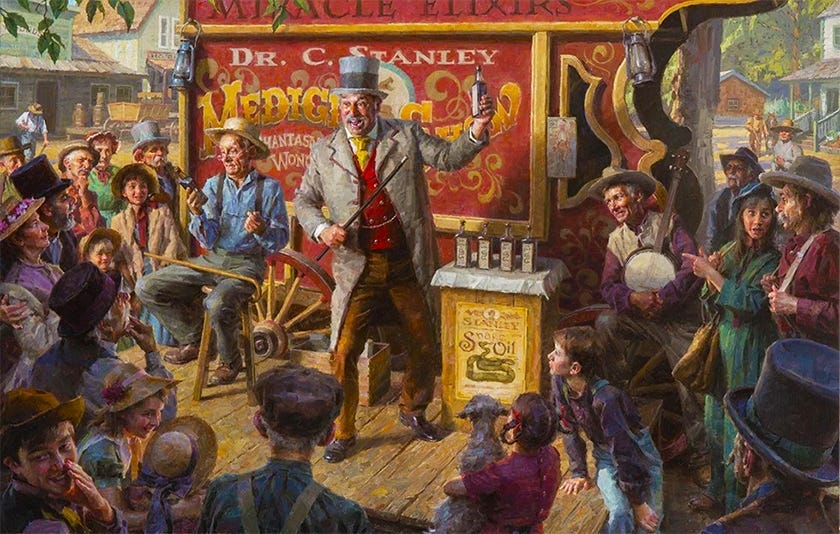

Rapturists. Every last one of them. So while it’s tempting to marginalize those who embrace Rapture Ideologies, to think they only show up preaching fire and brimstone or wired up to suicide vests, the stark reality is they’re all around us: wearing black mock turtlenecks and fleece vests, chatting on iPhones, tuning in to Doomsday Preppers on cable TV.

***

If we do nothing, and Rapturists of all stripes have their way, we’ll be left to play Mad Max on an exhausted planet while a handful of tech titans upload their consciousness to computers or catch one of the last flights into space.

Or maybe we’ll get swept up in a Middle Eastern war en route to the Last Judgment of Revelation, or the rise of a jihadi caliphate.

None of those sound especially good.

Any one of these scenarios should provoke, at a minimum, spirited debate about our collective future, and, at a maximum, serious concern. But almost no one seems to be paying attention.

We’ve ceded the airwaves, news cycles, and initiative to a handful of ideologues and zealots. The longer this goes unaddressed, the worse it’s going to get.

“A renewal of apocalyptic belief is underway that is unlikely to be confined to familiar sorts of fundamentalism,” John Gray, London School of Economics philosopher, writes in Black Mass: Apocalyptic Religion and the Death of Utopia.

“Along with evangelical revivals there is likely to be a profusion of designer religions, mixing science and science fiction, racketeering, and psychobabble, which will spread like internet viruses. Most will be harmless, but doomsday cults . . . may proliferate as ecological crisis deepens.”

Here’s the dangerous and seductive part: the harder and scarier the challenges we face—whether sociopolitical, economic, epidemiological, climatic, or spiritual—the more tempting it is to believe we can leap-frog the whole train wreck.

When buying into one of those stories, we tell ourselves two lies: The first is that there’s no hope for the world as we know it. The second is that, against all odds, we’re one of the lucky ones who get a Golden Ticket to the other side.

***

In study after study, religious moderates and secular humanists around the world share a desire for stability and prosperity. Most people, across cultures, just want to live in peace and see their children get a chance for a better life. That desire unites us. Atheists, Muslims, Christians, Confucians, Buddhists, Jews, Hindus, and hipsters—all just want a shot to die in their sleep, happy and surrounded by grandchildren.

It’s always been this way.

But Rapturism sees the world in fundamentally different terms— it’s an exponentialist approach, driven by a conviction that this world is beyond repair and that any pain and suffering in this world will be redeemed by accelerating the transition to the next.

When the End is literally heaven on earth (or beyond it), the Means are always jus- tified.

Here’s the problem with that logic: Even if you are a devout jihadi, or Christian Zionist, or have prepaid for your first-class ticket to SpaceX Mars Edition, you amount to less than 1 percent of the Earth’s population.

That means a fractional minority of humanity has seized the wheel of our collective future. And your “redemption” means everyone else’s likely annihilation.

So what about the 99 percent—the rest of us? What about that great silent majority of people around the world who just want a decent chance to keep on keeping on?

***

While surveying the wreckage of World War I, “the war to end all wars,” William Butler Yeats penned one of the classics of modern literature, his poem “The Second Coming.” In fevered imagery, it overlaid biblical themes onto a traumatized Europe and reflected on what was to come.

“Surely some revelation is at hand; / Surely the Second Coming is at hand,” Yeats wondered. “And what rough beast, its hour come round at last, / Slouches towards Bethlehem, waiting to be born?”

It’s been a fixture of popular culture ever since, giving Nigerian author Chinua Achebe the title to his seminal work Things Fall Apart, and Joan Didion the name of her collection of essays Slouching To wards Bethlehem. It even inspired an episode of the HBO series The Sopranos titled “The Second Coming.”

A few years ago The Wall Street Journal reported, “Terror, Brexit and U.S. Election Have Made 2016 the Year of Yeats.” A Dow Jones semantic analysis of online content revealed that there were more people around the world referencing the line “things fall apart, the centre cannot hold” in that tumultuous election year than at any time in the prior thirty years.

Since then the centrifugal forces that Yeats warned of and the number of things falling apart have only increased.

“The best lack all conviction,” he wrote, “while the worst are filled with a passionate intensity.” And that’s precisely where we find ourselves right now. A huge number of good-hearted, hardworking, live-and-let-live humans are having their fates decided by a passionately intense minority dedicated to capital “R” Rapture ideologies.

So how do the best of us, how do the rest of us rekindle an intensity passionate enough—our lowercase “r” rapture—to counterbalance the extremes, and take a stand for our lives and our future?

If we can do that, we’ve got a shot at solving the big problems we face. We can mend where we’re broken, reconnect with each other, and live lives of passion and purpose. And if we can’t?

Well, the dustbin of history has swallowed civilizations far older and fancier than ours.

(if you’re curious about the rest of this story and what to do about it, check out Recapture the Rapture: Rethinking God, Sex and Death in a World That’s Lost Its Mind)

"So how do the best of us, how do the rest of us rekindle an intensity passionate enough—our lowercase “r” rapture—to counterbalance the extremes, and take a stand for our lives and our future?"

Prudent preparation of logistical items, trusted networks of resourceful humans at the local level, and a sense of the sacred grounded in humility and a pluralistic grace.

Ya’ll. People are figuring this stuff out and have been building towards a grassroots non-rapture, concretely, in the current paradigm, since Katrina. Look up Common Ground Collective. Common Ground Collective birthed Mutual Aid Disaster Relief, a network of people who are self empowered to work emergently in emergencies. Yes, we vet people. But also, mutual aid systems emerge everywhere. Look at micro-finance systems. Look at every disaster everywhere, look at protest encampments and even some homeless encampments. The problem seems to be looking towards the power structures and influencers amongst the privileged in society . You know… the meek shall inherit the earth… yeah?