These days, it’s seeming like more and more conversations about the state of the world include someone tentatively, almost plaintively asking “Is there something wrong with us? Did we take a wrong turn somewhere?”

Questioning our basic goodness and direction might be sparked by the most recent tragedy in Africa, the Middle East or Eurasia.

Or it could be prompted by a particularly inane spat in the culture wars.

Or the latest gloomy forecast on climate, politics, economics or mental health.

Or maybe just some gradually creeping malaise, that somehow, over the last decade, we seem to have so irrevocably lost the plot that we might need to scrutinize the entire story we’ve been living in.

Regardless of the data point, the implication remains the same:

We seem to be fucking things up almightily, and it’s increasingly looking like we kind of deserve what’s coming down the pike.

After all, we know better.

So how come we can’t seem to do better?

We’re panning back from the shared narrative of the last 75 years, where most people in most places bought into some version of global markets = heightened prosperity, and everyone deserves a fridge, an air conditioner, a motorbike and a cell phone (or much more if you live in the Global North)…

And we’re asking the question behind those stories too.

Are we on the right track? Is the way forwards, even faster, or backwards to a fork in the road we must’ve somehow missed?

Given our moment in history and the overwhelming evidence that something (or many things) aren’t quite right, we’re still weirdly stuck repeating the same old rallying cry.

It echoes from rooftops to retweets…Growth is Good. The way forwards is faster!

Degrowth, or slowing our relentless pace of having, being and doing more, is looked upon as an affront, an ideological assault on the Modern Age.

C.P Snow wrote about it decades ago. Marc Andreessen and others have been offering bullish updates lately.

“It is all very well for one, as a personal choice, to reject industrialization—do a modern Walden, if you like, and if you go without much food, see most of your children die in infancy, despise the comforts of literacy, accept twenty years off your own life, then I respect you for the strength of your aesthetic revulsion.

But I don't respect you in the slightest if, even passively, you try to impose the same choice on others who are not free to choose. In fact, we know what their choice would be. For, with singular unanimity, in any country where they have had the chance, the poor have walked off the land into the factories as fast as the factories could take them.”

When environmentalists or social activists suggest we might need to pump the brakes on all that unchecked consumption, critics accuse them of everything from ushering in a new Dark Ages, to callously denying poor, starving mothers in Africa a chance for their children.

“Grow the pie even bigger, and there’s no need for portion control!!!” the boosters insist.

Augustus Gloop would be proud.

This barely bears pointing out, but those in this default Pro-Growth camp remain hooked on the Narrative of Progress.

You know the one, “We started huddled in caves and now we’re kicking it in high rises!”

#suckitmonkeys

We suffered from too much horseshit in our cities, and then invented cars.

We endured the “London smog” of coal-fired factories, and then discovered liquid fuels.

We were running out of food and farmland and then concocted synthetic fertilizers (without which half of the world’s population would be dead!).

There’s nothing we got ourselves into that we can’t engineer our way out of!

But what gets lost in this clumsy either/or Progress narrative are all the places where we’re half right, and half wrong.

And if we keep blindly defending the good parts while excusing the bad parts, we’re gonna come unglued altogether.

Instead, we should engage in a comprehensive act of Conscious Decoupling at three levels of our existence.

Not the Goop-y “conscious uncoupling” of Gwyneth and the Coldplay guy

But three crucial instances of decoupling what we’re doing from where we’re heading.

Let’s take them one at a time.

First: we have to decouple vital technological innovation from mindless overconsumption.

In most Pro-Growth defenses, the very same whiz-bang technological innovation we need gets 100% conflated with fat-fuck plastic-wrapped fast food obscenity (that we don’t need).

We don’t think to decouple the healthy innovative parts of our society and markets from the completely unhealthy excesses it’s accidentally generated.

This isn’t remotely complicated. And it needed to happen yesterday.

More conscious innovation. Less mindless consumption.

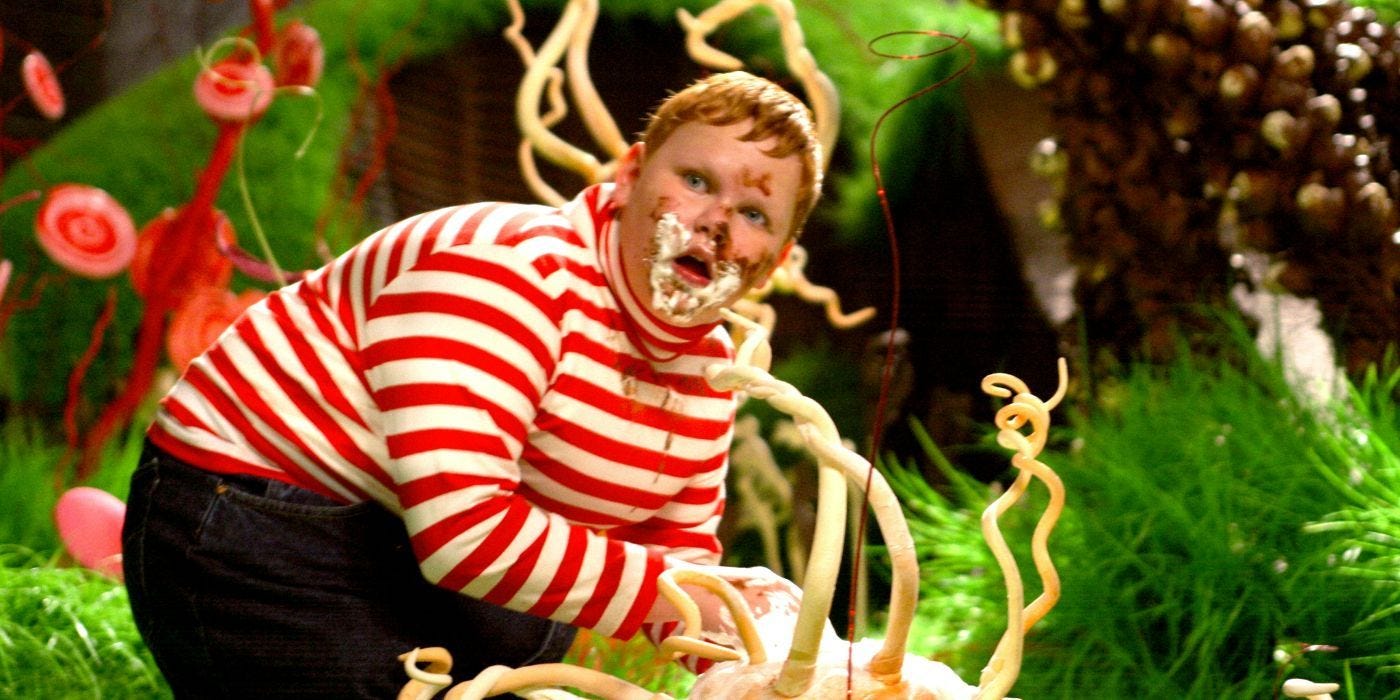

Next, we need to decouple carbon consumption from GDP. It’s never been done in all of human history. We’ve always burned increasing amounts of ever-denser carbon to fuel the rocket-ship of Progress.

It’s not 100% clear we even can.

But now, with a combination of nuclear energy (which technically doesn’t burn carbon) and renewables like wind, hydro and solar, there’s the tiniest inkling of maintaining our standard of living (GDP) while at the same time, reducing our carbon footprint.

Optimists like Hannah Ritchie of Our World in Data are insisting that in some Western European countries and North America that we already have begun this decoupling.

Skeptics suggest that we’ve just gotten better at outsourcing our dirty work to the Global South.

Optimists counter those arguments and suggest that even factoring in off-shoring, we’re still starting to see it. Pessimists double down on their suspicions.

We’re not solidly sorted yet.

But one thing’s for certain–until wind turbines, solar farms and hydroelectric projects can be created using the energy they generate, they remain elaborately subsidized (with carbon) science fair projects.

And the very promise that we can have our GDP cake and not heat it too…well that’s some seductive motivated reasoning we should seriously scrutinize before believing.

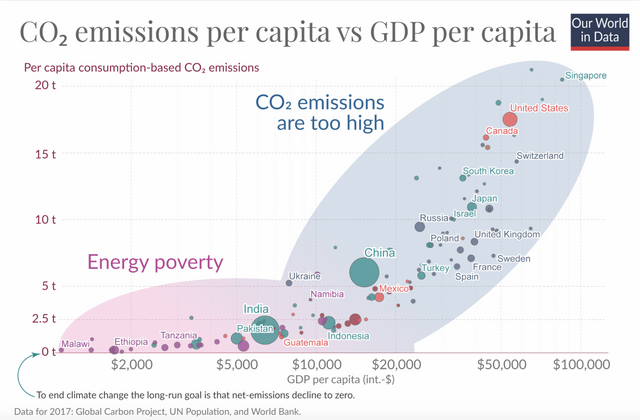

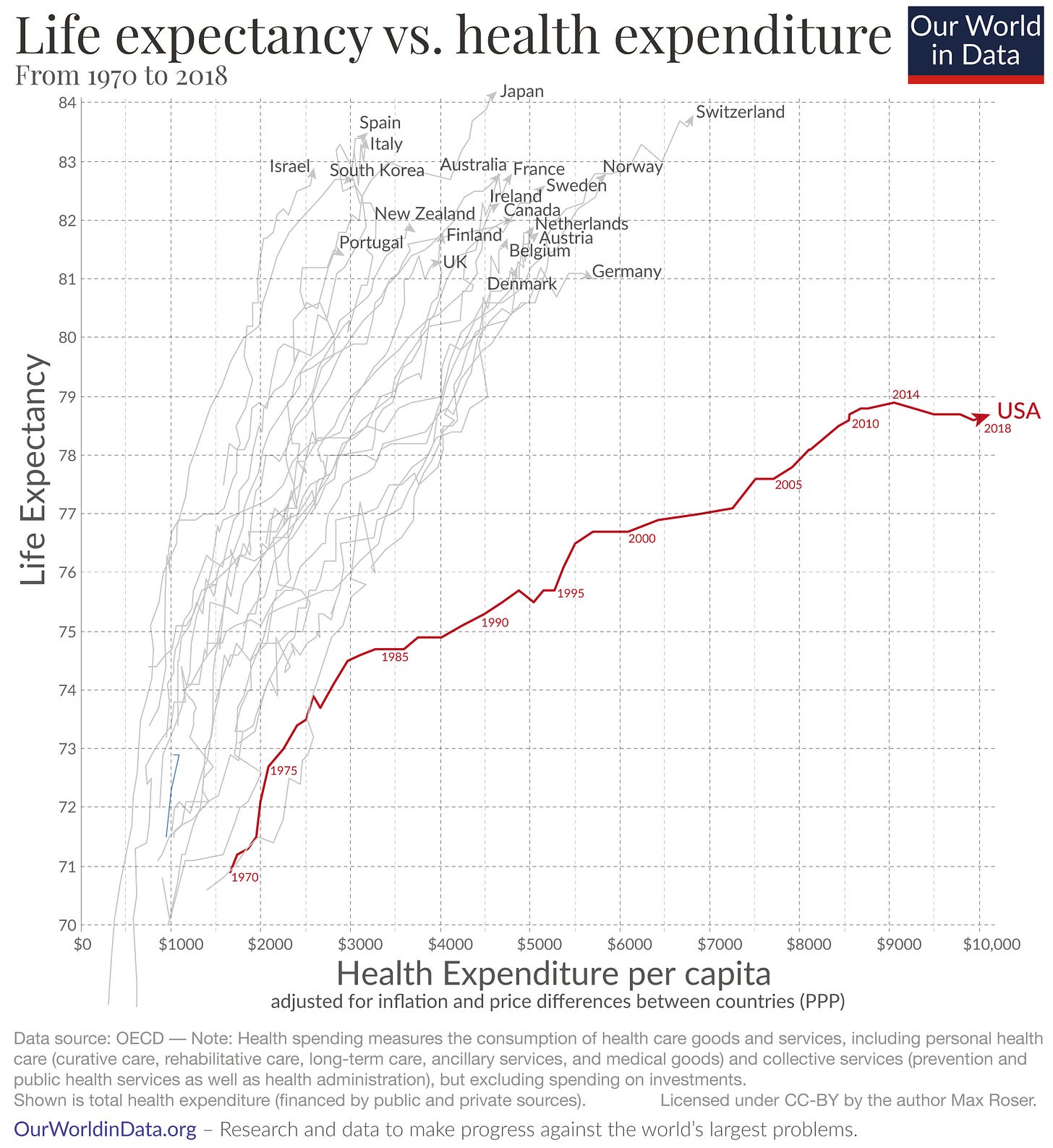

Which brings us to our third and final move: we need to decouple GDP from quality of life.

It’s abundantly clear that the correlation between what we spend and how we live has broken.

We’re spending more and more, but not feeling better and better.

The United States burns more than twice as much energy as its Euro counterparts but does not enjoy twice the standard of living.

In fact, it ranks in the 20-40s measured against far smaller, poorer countries, across all sorts of broadly accepted measures of national success, ranging from infant and maternal mortalities, literacy rates, violent crimes, life expectancy, etc.

It’s a political embarrassment.

And if you’re tracking our level of consumption against planetary boundaries, or the bottom 4 billion humans alive, it’s an ethical and ecological abomination.

But here’s the kicker that calls the entire Progress Narrative into question: a recent study assessing quality of life of industrial nations compared to remaining indigenous peoples found that in several instances, the indigenous tribes reported stronger quality of life than the developed countries. (only the top industrial countries were comparable)

It is often said that money can’t buy happiness, yet many surveys have shown that richer people tend to report being more satisfied with their lives. This tendency could be taken to indicate that high material wealth—as measured in monetary terms—is a necessary ingredient for happiness. Here, we show survey results from people living in small-scale societies outside the globalized mainstream, many of whom identify as Indigenous. Despite having little monetary income, the respondents frequently report being very satisfied with their lives, and some communities report satisfaction scores similar to the wealthiest countries.

Now, at first glance, that might lead to some Romantic Noble Savage nostalgia, “ah, those folks live close to Mother Nature, they’re communing with Source, back to the land, etc.”

But then you remember the colonial history of the last five hundred years.

And you realize, “Holy shit! These folks (and their parents and their parents and their parents) have been on the receiving end of centuries of horror, dislocation, degradation, pandemics, coerced labor, ecological exploitation, cultural erasure…you name it, they’ve endured it.

And at the end of all of that, they’re still enjoying a higher quality of life than many of us!”

That would be the equivalent of a van full of indigenous folks surviving a roll-over at highway speeds, dragging themselves out of the wreckage, lacing up their tire strap sandals, and still kicking our asses in the 100M dash!

It’s utterly mind-bending and humbling.

Kohei Saito, an economist and author of Capital in the Anthropocene, is a proponent of Degrowth Communism. He has some thoughts on the initial baby steps we’d need to take to get a bit more back in balance.

Ban private jets. Get rid of advertising for harmful goods and services, such as cosmetic surgery. Enact a four-day workweek. Encourage people to own one car, instead of two or three. Require shopping malls to close on Sundays, to cut down on the time available for excessive consumption. “These things won’t necessarily dismantle capitalism,” he said. “But it’s something we can do over the long term to transform our values and culture.”

Really, Saito’s “Degrowth Communism” proposals are closer to Democratic Socialism a la Bernie Sanders than any Marxist-Leninist thingy But you’ve gotta give it to him, he’s got an ear for the catchy title.

And while boosters of Progress will insist that any efforts at all to pump the brakes are wrong-headed, anti-humanist and doomed to fail, I think it’s fair to say we’re in a baby/bathwater situation here.

The baby of western techno-industrial civilization is all the awesome innovations we have developed and can use to solve the pernicious challenges of living as monkeys with clothes on this little blue marble.

The bathwater is mindless commercial consumption, literal and digital obesity, and the spewing of carbon calories all over the place like there’s literally no tomorrow.

We should chuck the lot of them.

And then there’s the biggest baby of them all we’ve got to hang onto…the eternal question of what does it mean to live a good life as a human being?

Beyond GDP, smart phones, literacy rates and health insurance, what does a good life, cradle to grave, even look like?

Because you could make a case that this is the only real question that matters. All the standard of living metrics the World Bank and U.N. spit out are just crude proxies attempting to track this deeper core question.

On that count, those indigenous tribes surveyed can help us see that The Good Life doesn’t require excess oil or dollars. In fact, it’s quite often antithetical to unchecked consumption.

What does it take?

Family and community connection.

Locally grown foods.

Rituals and celebration.

Connection to place and nature.

So in the final analysis, the answer is simple.

We may need to decouple our civilization from our wasteful ways, and we almost certainly need to decouple our spending from the burning of fossil fuels…

But we need to redouble our innovations, and re-couple our connections.

To ourselves, our communities and the places we all call Home.

Thank you for this piece. Reminds me of the book Sacred Economics by Charles Eisenstein. What we see on the macro level is a reflection of each of our individual insatiability. When we lose the ability to find pleasure and excitement in "ordinary" things, we're driven to heighten the stimuli and making/consuming more supports this drive. Yes, decoupling GDP from quality of life is a concrete measure. But to get there, it takes a fundamental shift in our motivation from "I need more excitement" to an accessible but rarely tapped state of gratitude of "I'm excited to be alive." Indigenous tribes connect deeply with day-to-day experiences and in so doing, they are connected to Life. Until and unless the underlying drive behind consumption transmutes, we will find ourselves hungry even when we are beyond fed.

Can we decouple energy and resource use (and by extension, pollution) from life happiness? Not just relatively, but absolutely? This is the central question of our civilization, but not often talked about. I appreciate all the points you bring up Jamie. Just last week I published an article putting resource use and environmental disruption into a simple equation. My intent is to assist in understanding the three broad factors we have the potential to change in order to use less and degrade less while still thriving, individually and collectively. Of course these three factors are themselves made up of many other factors. The TL;DR is:

environmental disruption = [resource intensity of producing goods] x [consumption of goods per person] x [population]

I like how you phrase the 3 levels of "Conscious Decoupling." Innovation needs to be focused on increasing the efficiency of existing processes or replacing old processes and products with ones that are less resource intensive, rather that making more cool new gadgets we don't necessarily need. I would add to your second point that we need to decouple total resource use and all forms of environmental pollution from GDP, not just CO2.

Your third point on decoupling quality of life from GDP is arguably the most challenging, since it's hard to measure. If it's hard to measure and find patterns, it's hard to change. This is the area I feel your unique way of thinking could help us the most. Your teachings provide ways of doing this. The trick is translating that Homegrown Human blueprint for widespread adoption. It's a fine line to convince a person to live more and consume less without meeting ideological resistance, but you have a unique ability to do so. Thank you for your work Jamie.