Cheat Code to the Mysto

Laughing Gas Is NO Laughing Matter! (Seriously)

Quick Note: later today we kick off our only Power of Story course for writers and speakers in ‘25. Six weeks. Best tools plus new module on how to use best of AI. Grab a spot here if interested.

(following post typed entirely by a clever monkey with fat fingers, Zero AI inputs)

***

Seems like Lockdown prompted an “inward turn” that many of us haven’t fully unwound from yet.

People all around the world dived into their laptops and encrypted chats to “do their own research” (with results that will rock the political and social fabric for years to come).

Telemedicine and a so-close-you-could-almost-see-it-from-here psychedelic renaissance formed an unholy alliance. Lots of folks ended up smacked out in their living rooms on ketamine.

But along the way, another little vice popped up, and then went viral on TikTok (and hip hop).

Ye Olde Whyppette.

Or as the Land of Oz likes to call ‘em, nangs.

Because naaaannnnggggg is the sound you hear in your ears right before passing out from huffing too much laughing gas.

A bit of onomatopoeia from those poets from the Land Down Under who brought us such classics as The Great Sandy Desert, the Snowy Mountains, the Crooked River and the Ninety Mile Beach.

(“I mean, I dunno, Bruce, what should we call that great big fuckin’ sandy desert we just walked through? Ah, great idea! How ‘bout those big fuckin’ mountains with all that snow on ‘em! Beauty!” Last question, we’ve been walking end to end on this beach for ninety miles or more and I’m absolutely knackered…)

But it’s not just our Aussie brethren who are huffing the stuff. The youth of that dismal isle Britannia are knocking it back too.

And the US has apparently hit peak gas, with the advent of Big Gulp Super Size versions that hold the equivalent of a small SCUBA tank.

In the past month, both New York magazine “The Next Epidemic is Blueberry Flavored” and the august Atlantic “The Illegal Drug at Every Corner Store” have both published pieces on the phenom.

Much of the coverage is, understandably from the public health side of things. But not very much of it gets past the headlines to understand the history, the neurophysiology, and the experience that so many keep coming back to so often.

This is an excerpt from Recapture the Rapture: Rethinking God, Sex and Death for a World That’s Lost Its Mind that unpacks the cultural history and neuroscience in a bit more detail. Hope you enjoy.

(plus the wildest venture capital story of the 19th century)

How the West Was Fun

Nitrous oxide is an inorganic compound that’s been off-gassing from the atmosphere, soil, and oceans for eons.

It’s one of the more interesting members of the nitrogen family. While only a slight variation of the inert nitrogen that makes up roughly 80 percent of the air we breathe, this oxide has a fundamentally different effect on our nervous system.

Nitrous soothes nerves and eases pain but also gives rise to experiences stranger—and potentially more therapeutically useful—than most Schedule I substances.

Today, we have new insights from the field of neuroscience into why it does what it does. So in any survey of respiration and the potent impact it can have on our bodies and brains, we’d be remiss if we didn’t discuss exactly what happens when you take two atoms of nitrogen, bond them to one atom of oxygen, and inhale deeply.

***

On October 14, 1833, The Albany Argus, a small-town paper in upstate New York, published a curious quarter-page advertisement on behalf of the local museum.

It invited loyal patrons to attend an exhibition by a “Dr. Coult of New York, London and Calcutta” on the effects of “Exhilarating Gas.” This substance, the ad proclaimed, produced the “most astonishing effects on the nervous system,” ranging from laughing and dancing to wrestling and boxing.

It went on to assure prospective attendees that Dr. C. was a “practiced chemist so no fears need be entertained of inhaling an impure gas” and that ladies and gentlemen “of the first respectability” had all enjoyed its “highly pleasurable effects without debilitation.”

The advertisement closed with a zinger: “Those persons who inhale the gas will be separated from the audience by means of a net so that spectators . . . will be perfectly free from danger.” Admittance was only 25 cents.

Two weeks later, Dr. Coult appeared before a packed house. Nervous volunteers of both sexes stepped up to inhale from his contraption, tackling each other, shouting out epiphanies, and dissolving into giggles.

Townsfolk could talk of nothing else for weeks. But it turned out that “Dr. Coult of New York, London and Calcutta” wasn’t a practiced chemist at all—not that anyone really cared.

He was a nineteen-year-old kid from next-door Massachusetts.

In fact, Coult wasn’t even his real name. It was Colt. Samuel Colt, the man who’d go on to become the most famous and wealthy entrepreneur of his age.

A few years before his Albany visit, Colt had been expelled from Amherst Academy. His father, figuring his unruly son could do with a “hands-on” education, signed him on as a ship’s boy on voyages that included the aforementioned stops in London and Calcutta.

According to his later memoirs, Colt became fascinated by the ship’s wheel and how “regardless of which way the wheel was spun, each spoke always came in direct line with a clutch that could be set to hold it.”

It gave him the idea to transpose that mechanism to a pistol, creating a revolving barrel that could hold multiple bullets at a time. While at sea, he whittled two prototypes out of wood.

But when he returned home, his father was unimpressed with the concept. If he wanted to take his idea to market, Samuel realized, he’d have to raise the funds himself.

Which is when the enterprising young inventor conceived his alter ego, “Dr. Coult.” In less than two years of hosting exhibitions like his sold-out stand in Albany, he raised the seed capital to secure the patents for what became the iconic Colt .45.

That fast-action pistol turned the tide for the Texas Rangers against the Comanches and sat on the hip of every sheriff, gunslinger, and cavalryman from Deadwood to Little Bighorn.

Laughing gas, a simple combination of two common elements, prone to producing curious effects in those who breathed it, ended up bankrolling “the Gun that Won the West.”

As we’ll see, Colt’s story isn’t even the strangest in the annals of nitrous oxide.

***

Nitrous oxide had been known to experimenters for some time before Colt latched on to it. The gas was first synthesized in 1772 by the English chemist Joseph Priestley. A few decades later, James Watt, of future steam engine fame, invented a machine to produce “Factitious Airs.”

In 1800, Humphry Davy published his definitive work Researches, Chemical and Philosophical, which correctly identified the gas as a possible pain reliever useful in surgery and coined the name that stuck: laughing gas.

For the first half of the nineteenth century, it enjoyed popularity at “laughing gas parties” for the British upper class. Socialites gathered at country estates and London town houses to take turns inhaling the vapors and enjoying each other’s reveries and insights.

The poets Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Robert Southey took part, as did Peter Roget of Roget’s Thesaurus and Thomas Wedgwood, son of the famous potter.

As these parties crossed the Atlantic, Samuel Colt capitalized on the trend. But it wasn’t until forty years after his Albany exhibition that nitrous oxide truly met its match in someone who could get past the laughs and see its potential as a tool of serious insight.

Harvard psychologist William James was first introduced to the gas in the 1870s and found it instantly illuminating. At the time, he was battling back from a serious depression that had nearly cost him his career and life.

Trained as a physician but increasingly drawn to philosophy and religion, James subscribed to a school of thought known as pragmatism. This worldview hinged on the stark idea that there are no universal truths or constants in the world, only more or less practical working assumptions.

His initial experiences with nitrous oxide freed him from his rather bleak materialism and emotional despair. He became, by his own description, a rational mystic.

“I strongly urge others to repeat the experiment. . . . With me, as with every other person of whom I have heard, the keynote of the experience is the tremendously exciting sense of an intense metaphysical illumination. Truth lies open to the view in depth beneath depth of almost blinding evidence. The mind sees all logical relations of being with an apparent subtlety and instantaneity to which its normal consciousness offers no parallel.”

Those insights made such an impact that scholars separate James’s writings into clear “before laughing gas” and “after” categories.

He admitted in his 1902 Varieties of Religious Experience that “my impression of its truth has ever since [experiencing nitrous oxide] remained unshaken. It is that our normal waking consciousness . . . is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different.”

That conviction catalyzed his work as arguably America’s greatest philosophical mind. James’s forays into nitrous spawned two of his key contributions to academia: the first that direct experience is more valuable than religious doctrine or dogma and the second that there is no singular and absolute truth—only a multitude of perspectives.

This mystical pluralism foreshadows much of what we are still exploring over a century later and gives us a tantalizing hint of what we are searching for: a way to harness the peak experience of lowercase “rapture,” without veering into certainty and dogma.

James just beat us to it.

Despite the inspirational benefits that James received from his explorations with the gas, he had a persistent problem—how hard he found it to hang on to its quicksilver insights.

“Only as sobriety returns,” he lamented, “the feeling of insight fades, and one is left staring vacantly at a few disjointed words and phrases, as one stares at a cadaverous-looking snow peak from which sunset glow has just fled, or at a black cinder left by an extinguished brand.”

Because of this persistent gap between what he could glimpse and what he could retain, and his fear that his colleagues would mock his flights of fancy as “unscientific,” James discontinued his use of the substance. He spent the rest of his career trying to map with reason what he had first discovered in the realm of revelation.

James wasn’t the only prominent explorer to find those insights hard to hang on to. It happened to Winston Churchill too, quite literally, by accident.

While on a 1931 speaking tour of New York, Churchill got run over on Fifth Avenue. He had forgotten that traffic went the other way in the United States and exited his cab straight into an oncoming car.

He was rushed to Lenox Hill Hospital, where Dr. Charles Sanford, one of the very few physicians specializing in anesthesiology in the early 1930s, was on duty. In what may have been one of his first encounters with the gas—but clearly not the last—Churchill experienced something remarkably similar to what James had before him.

“With me, the nitrous oxide trance usually takes this form,” Churchill later told the Daily Mail, “the sanctum is occupied by alien powers. I see the absolute truth and explanation of things, but . . . it is beyond anything the human mind was meant to master.” With typical dark humor, he went on to note, “depth beyond depth of unendurable truth opens. I have therefore regarded the nitrous-oxide trance as a mere substitution of mental for physical pain.”

Despite the public revelations of academics and statesmen like James and Churchill, the mysteries of nitrous oxide remained largely underground. The notion that the gas’s genius always disappeared on return to sobriety led most observers to dismiss it as a tool of serious inquiry.

By the end of World War II, “laughing gas” had established itself as a benign and commonplace anesthetic. From dentist chairs to doctor’s offices to birthing rooms, the compound was used to calm the nerves of kids getting fillings, soothe the pain of mothers delivering babies, and ease the minds of patients sedated for surgery.

The World Health Organization found it so useful it even placed it on its List of Essential Medicines. “It is a cerebral depressant and produces light anesthesia without demonstrably depressing the respiratory or vasomotor centre,” the WHO explained, acknowledging rather blandly, “induction is rapid and not unpleasant although transient excitement may occur.”

Since then, nitrous oxide has gone on to play a somewhat schizoid role as a harmless sedative administered by white-coated professionals and as a casual diversion for those seeking its “transient excitement”— often to the point of abuse.

In 2016, the Global Drug Survey reported that the United Kingdom had the highest instance of illicit use of all nineteen countries studied. Overall, nitrous oxide now ranks as the seventh most popular recreational drug in the world.

In the United States, The Village Voice investigated the Nitrous Mafia—a gang of ruffian black marketers who traveled the music festival circuit selling giant balloons of “hippie crack” to eager concertgoers. “It’s an instant rush of pure euphoria,” fan Justin Heller told the Voice, “but it only lasts for 30 seconds or a minute, and then you want it back.”

When asked why he chose to partake, another enthusiast explained, “Because nitrous is the best orgasm I’ve ever had in my life.”

Between these two poles—helpful anesthetic or mindless diversion— the most interesting thing about this substance keeps getting forgotten.

From Samuel Colt proclaiming it “the highest of all possible heavens” to William James noting its “intense metaphysical illumination” to Winston Churchill acknowledging it as the “absolute truth and explanation of things,” we’ve overlooked the most obvious question, again and again.

What were all those gas-drunk explorers actually laughing about?

To be sure, it’s not the high-pitched giggles that helium provides.

It’s not the goofy euphoria of cannabis or even the spill-your-drink buzz of a few beers. If we are to take the accounts of early explorers at face value, the laughter of laughing gas comes from nothing less than sheer gobsmacked amazement. Perhaps the only rational response to nearly instantaneous revelation.

With nitrous oxide intoxication, the mechanism of action is fundamentally different from the disinhibition of alcohol or other common inebriants.

For starters, nitrous oxide triggers three of the six neurochemicals central to almost all non-ordinary states of consciousness— norepinephrine, dopamine, endorphins (the other three are anandamide, serotonin, and oxytocin).

That alone is more than enough to qualify it as a “molecule of interest” in any investigation of state-shifting tools.

Its anxiolytic, or anti-anxiety, qualities stem mainly from its bonding to dopamine and benzodiazepine receptors (think Valium and Xanax); its analgesic, or pain-relieving, properties come from the endorphins or opioids it releases (think morphine or OxyContin).

You’re carefree and pain-free, and feel awesome. That combination puts nitrous oxide squarely in the ranks of go-to comfort drugs but doesn’t explain how it inspired Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poetry, William James’s philosophy, or Winston Churchill’s reveries.

Fortunately, in the last ten years, we’ve learned more about the biological and chemical underpinnings of the nitrous experience than we’d gathered over the past two centuries.

The Amazing Nitrogen Family

As we track down what the World Health Organization so blandly described as the “transient excitement” that nitrous oxide produces, there are a few more links to connect.

They bring us all the way back to William James’s stomping grounds at Harvard Medical School. There, Herbert Benson became the leading authority on the body’s biological response to peak experience.

His quest led him to a deep study of the nitrogen family and nitrous oxide’s kissing cousin, nitric oxide. This neurotransmitter carries away stress chemicals from the brain and serves as a vasodilator in the body—Viagra, which directly boosts nitric oxide production, makes use of this tidy little side effect.

Nitric oxide (NO), identical to nitrous oxide (N2O) but for one nitrogen atom, is, according to its foremost researcher, “the catalyst of physical, mental, and even spiritual experience.”

That’s tantalizingly close to the subjective reports of nitrous users through the centuries. And here’s where it gets really interesting: once inside our lungs and brains, the two gases behave similarly. When a user inhales nitrous oxide, enzymes in the brain break it down into nitric oxide.

It then zips across the blood-brain barrier and up and down our spinal column, faster than thought.

Just across town from Benson’s lab, researchers at MIT have discovered a neuroelectrical explanation for some of this molecule’s unique effects.

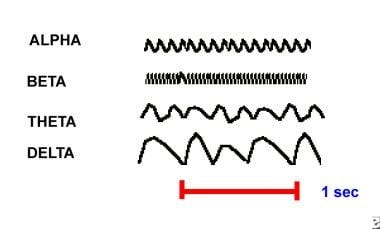

As reported in the journal Clinical Neurophysiology, Dr. Emery Brown found that when subjects were tracked with an electroencephalogram (EEG) while inhaling a fifty-fifty gas blend of “nitroxygen,” something fascinating happened to their brain waves.

They shifted from high-frequency beta waves (12.5–30 HZ—the kind normally associated with alert thinking) into extremely low- frequency delta waves (0.1–4 Hz—the kind normally associated with deep and dreamless sleep).

And there was another unusual thing about those readings: the amplitude, or height, of those delta waves was double what they normally are when we’re sleeping.

“We literally watched it and marveled because it was totally unexpected,” Brown told MIT News. “Nitrous oxide has control over the brain in ways no other drug does.”

That’s a pretty bold statement coming from a world-class researcher with access to an unlimited medicine cabinet.

This was such an unexpected finding because in EEG research, delta waves are very much the redheaded stepchild.

Sleep researchers pay a bit of attention to them, but not nearly as much as they do to REM cycles, the rapid eye movement where most dreaming happens.

Waking EEG studies tend to focus on beta waves—where we do most of our problem-solving and cogitating—or alpha and theta frequencies—where, if we’re lucky or skilled enough, we experience flow states, hypnagogic states (those moments in-between waking and dreaming), or deep meditative states.

But waking delta? That’s an underreported story. And it just might hold the key to unlocking nitrous oxide’s secrets.

“If you see slow EEG oscillations,” Brown says, “something has happened to the brainstem.” Without those excitatory signals from our brain stem lighting up higher brain functions, you usually fall unconscious and into deep delta-wave sleep (or anesthesia).

Except with nitrous oxide, you don’t fall asleep. You’re awake and aware of the experience. You even have some ability to steer. It’s like backdoor lucid dreaming.

Brown’s team uncovered another detail, one that explains why James and Churchill both experienced sudden insight followed by frustrating amnesia. The delta waves only last a few minutes, after which the brain returns to normal.

“These slow-delta oscillations begin approximately 6 min after the switch [to breathing 50/50 nitroxygen] and last from 3 to 12 min,” Brown explained, “before returning to the beta and gamma oscillations.”

Even with continued exposure to the gas, that three-to-twelve-minute window of waking delta is all you get, before brain activity adapts and normalizes.

Brown hypothesizes that nitrous molecules exert this remarkable control by binding to receptor sites in the thalamus and cortex. This knocks out arousal signals from deeper down in the brain, allowing a full system reboot.

Delta-wave activity has also been shown in DMT and ketamine states—both experiences renowned for their otherworldliness as well as their access to robust amounts of salient information.

A new Stanford study published in Nature has shown that the dissociative or otherworldly effects of delta-wave EEG activity correlate directly with the antidepressant effects of ketamine therapy.

“This state often manifests as the perception of being on the outside looking in at the cockpit of the plane that’s your body or mind—and what you’re seeing you just don’t consider to be yourself,” Karl Deisseroth, the lead author, said.

When this team was able to use electrical impulses to stimulate patients’ brains into delta frequencies, they had that same dissociative experience, even without the drugs!

And those moments of “being on the outside looking in” appeared to alleviate depressive symptoms. More delta, in other words, less blues.

Another recent study has shown an additional positive element of delta-wave activity. In a sleep study researchers found that only during slow-oscillation delta waves is the intracranial pressure (ICP) low enough to allow cerebrospinal fluid to come in and “wash” the brain tissues of beta-amyloid plaque.

If you sleep poorly, or don’t get enough delta-wave cycling, the research shows you’re at a higher risk for early-onset Alzheimer’s and a host of other neurodegenerative conditions.

Regardless of what method we use to get there—ketamine, meditation, brain stimulation, or nitrous oxide —once we find ourselves in a waking delta-wave EEG state, the results are often profound.

Delta waves, it’s becoming clear, can mend our brains, spark our minds, and soothe our souls.

***

Taken together, the MIT, Harvard, and Stanford studies go a long way to explaining what William James was marveling about all those years ago.

Up until now, we’ve had only the halting accounts of users who, while insisting that something profound occurs in the spaces afforded by the gas, were never exactly sure what it was or why it kept happening.

As James lamented, “one is left staring vacantly at a few disjointed words and phrases.”

But today, we’ve got more tools in our kit.

The fields of comparative religion, optimal psychology, and neuropharmacology that James himself inspired give us more precise language and frameworks to interpret these experiences with.

Voice recordings and medical measurements allow us to capture more of the fleeting and dreamlike insights that slipped through his fingers so long ago.

Nitrous oxide knocks out conscious processing, accelerates pattern recognition, and boosts the signal of how fast we can think, dramatically. And it does it for anyone with enough wherewithal to retain what they learn.

This does not make it harmless—any more than the wine served at Communion absolves us from alcoholism and organ failure if abused.

But it does point a way forward when considering a move beyond “placebo sacraments” toward ones that more reliably deliver insight and inspiration.

When “Dr. Coult of London and Calcutta” decided to make a few bucks delighting bored bystanders with laughing gas, he couldn’t have known that what he was peddling would exceed his own hype.

By switching out the nitrogen in the air we breathe for a slight variation, we unlock worlds of information and inspiration normally inaccessible to us.

And it works for people experiencing pain, anxiety, and trauma, as well as those who want to plumb the depths of the human condition.

“No account of the universe in its totality can be final,” William James reflected, “which leaves these other forms of consciousness quite discarded.”

That’s a possibility that should take our breath away.

I think you need to add a warning that excessive use of nitrous leads to horrific brain damage. One of my friends sons can barely walk as a result. A kid who was an expert surfer and skateboarder now has the cognitive decline and balance of a 90 year old man. Please read up on this Jamie

https://www.google.com/search?q=nitrous+oxide+peripheral+neuropathy&ie=UTF-8&oe=UTF-8&hl=en-us&client=safari

One of the last times I had a nitrous session, back in the late 1980s, I took the wild notion to experiment with a variation on the old Cheech and Chong routine, about "seeing God" by "taking acid and listening to Black Sabbath sped up to 78rpm." Except that I tried that with one of John Coltrane's last LPs, Expression, and the solo piano Hammerklavier Sonata by Beethoven, performed by Alfred Brendel (incidentally recently departed, only a few days ago.) And instead of speeding up the 33 1/3 LP to 78rpm, I set the turntable to 45 speed.*

Long story short, I realized that I would never die. Sort of. That existence was infinite, and that all consciousness--including the part that I was leasing--partook of that infinity, In some sense. Not an easy concept to articulate. Not exactly testable as a hypothesis, either. But as a subjective experience, marvelous. Ineffable, yet somehow reassuring. A reassuring message, from the Beyond. But now that I know that or grok it or whatever--now what? The materially inflected plane is what matters. I feel no need to re-visit the experience. I get it. Part of the lesson is that the insight is a flash--a transient flash, at least given the limits of the human condition. Then there's the rest of life to deal with, in the aftermath of it.

That wasn't my last N2O experience, however. That was a few months later, in the parking lot of a Grateful Dead concert. (Wouldn't you know.) Weirdly, I had been given a specific caveat about using nitrous some months earlier in the same exact lot: I was walking around, huffing from a balloon of it, and someone advised me to be sitting or lying down or at least leaning against something while inhaling it. I sort of hand-waved the guy, and he repeated his warning: "I've seen people do face-plants and get serious damage from doing it that way. Broken bones in the face, nerve damage. Experienced trippers." So I finished the balloon after taking that precaution. But I cast his advice to the wind only a few months later, taking a big gulp of gas while standing unsupported, listening to a Dead tape jamming in the background, doing a neatly woven high energy version of "Maggie's Farm"...the music started sounding extra special good, the way it does under the influence of nitrous--and then the gas dropped me. The last thing I remember is someone behind me saying excitedly "that's what that nitrous'll do to ya!" ~~wum wum wum~~I came to on the pavement. Luckily, I hadn't fallen forward. My back had arched over, and I had hit the asphalt exactly on the top of my skull, right on my own crown chakra. The whole episode was over like that. "Maggie's Farm" was still playing when I came to. Didn't even get a bump on my head. But believe me, I was scared. That knocked some sense into me. And I quit using using N2O entirely soon afterward. (I think it was when I found out that nitrous is a pretty serious greenhouse gas--300 times as powerful as CO2. Yeah, I'm one of those eco-squares.) A superfluous indulgence. Anything worth getting from it, I had already gotten.

The coda to that stem-winding tale is that a few months after that balloon knocked me cold in Oakland, I was at another Grateful Dead show. I was chatting with a young couple I had just met,early 20s, both holding balloons. And I left them with the same advice that I had gotten a year or so earlier, about having a stable place to rest before inhaling, to keep from toppling over. They both looked at me with mildly bored distaste, the same way many Deadheads were inclined to react when the band picked "Day Job" as their encore--"oh, no, not that sermon again..." And then, without another word, they both got up from the grass with their full nitrous balloons. After they stood up, they both inhaled deeply, and ran off across the lawn, hand in hand.

"...tell you what to do, but I know that you won't..."

I've just read a Wired magazine story about frequent users of DMT. To each their own, but I've been there, too. I don't find a lot of application in the insights. Extra-dimensional elementals be extradimensional. I don't trust them.** 4-D is where the action is, for us humans. For all of its limitations, like bodily mortality. Material entropy is intrinsic to 4-D. Eternal infinitude of discarnate consciousness notwithstanding. Extra dimensions aside. The entropic conditions of the material world can be improved--they should be improved. Oh yes. But not conquered. A project to add some extra years of high functioning to the physical body of our animal bodies is a good thing, and likely doable. But the notion of elevating the material human condition to "live forever" is getting carried away. Even the imagination of it is limited by anthropocentricity. Extending or even restoring the peak of youth is a much heavier lift, but imaginable. But my intuition is that improvements that ambitious require that humans--humanity, as a shared community--be very good people, humble, kind, reverent, and otherwise true to the game, in the values sense. That's a pre-condition. Achieving a goal like that one isn't just a technical challenge.

Here's where both Meister Eckhart and Ludwig Wittgenstein recommend that I shut up.

*imo both of the aforementioned LPs still sound better at the original speed. The synthetic alteration doesn't produce a qualitative improvement. It's merely faster.

**the evidently very psychedelic ruling castes of New World civilizations appear to me to have been badly misled, by something or other.