Bob Dylan and the Secret Scripture

Redemption Songs for Everyone

Housekeeping/Invite: If you dig these essays and would like to jumpstart your own speaking/writing, we’re running an encore presentation of Power of Story: a six week digital training that starts first week in Feb. Super fun, practical and productive, from honing your Elevator Pitch, to nailing a TED talk to cranking out a 250 page book. Click here to check it out. –J

***

Onto some Dylan…

“Hey, hey, Woody Guthrie, I wrote you a song

About a funny old world that’s a-coming along

Seems sick and it’s hungry, it’s tired and it’s torn

It looks like it’s a-dying and it’s hardly been born”–Bob Dylan

If you have somehow missed the full frontal Oscar blitz campaign for the new Dylan biopic A Complete Unknown, you must be living under a rock.

And it seems like you can’t throw that rock without hitting some clip featuring the stars gushing over each other, sharing behind the scenes details on how they all learned to play and sing, or how much they admire Dylan himself as an American institution.

Despite some of the Dylan purists who sniff that the timelines don’t always match up, or that this is a sanitized, mythologizing account, it’s pretty awesome.

Timothee Chalomet disappears into his role as Dylan. Ed Norton is perfectly avuncular as folk icon Pete Seeger. Monica Barbaro is more beautiful and ethereal than the real Joan Baez. And Elle Fanning plays Dylan’s one and potentially only true love and muse with grace and grit.

The plot itself hinges on the pivot point when “Dylan went electric.” These days, that’s a shorthand for anytime an artist goes against what their fans or handlers want them to do, and instead takes a principled stand for following the Muse.

For Dylan it infamously happened at the ‘65 Newport Folk Festival. And in the movie, the Resistance are one Alan Lomax (famous musicologist and co-founder of the festival) and Peter Seeger (aforementioned banjo plunking folkie).

It’s a powerful snapshot of a moment in time (1961-1965) when the world was both on fire, and aflame. In those wild four years where Dylan wrote everything from Blowin’ in the Wind to Like a Rolling Stone, he was channeling something far bigger than himself.

He tapped into the electric current of American gnosticism that runs right through the music they all played and loved.

(and if you want to listen to arguably the most banging version of Like a Rolling Stone EVER, check this ‘74 barn burner with Robbie Robertson and all the boys of The Band. After eight years of not touring, Dylan and the boys come roaring back, raging against the machine and laying down some coked-up double time genius).

Here’s a story about those guys and more. About the American Songbook and its power to inspire and heal. In these fractured and fractious times, where we can’t seem to agree on anything, it points out a way forward for all of us.

***

One Fall in college, I went back home to visit my parents for a weekend, and I was listening to a Grateful Dead show on the stereo. As the band jumped into “Going Down the Road Feeling Bad,” my dad walked through the living room and started chiming in. He even added a few variations on the lyrics.

“Wait, how do you know this song?” I asked him. This was my newfound music, after all. It was countercultural, accessible only to those “in the know.” How in the hell did my dad know anything about the Dead?

“‘Going Down the Road’?” he asked. “That’s an old Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger tune. They called it ‘Lonesome Road Blues.’ Here, gimme a minute.” He brought out his old mahogany banjo, fiddled with the tuning pegs, and jumped into a finger-picking rendition.

It turned out that back in the early sixties, between tours of duty as a test pilot on aircraft carriers, my dad had been a part of the London folk scene.

That banjo he’d been playing for me had been given to him by Peggy Seeger, Pete’s kid sister. (It’s sitting next to me now as I write this, though I can’t play it half as well.)

My dad got up, rummaged for a minute through his musty record collection, and pulled out an album called Old and in the Way. The cover was a goofy cartoon of a jug band—but there, dead center of the picture, was a bearded dude sitting on a stool holding a banjo. Black haired rather than gray. Not quite as chunky as the psychedelic Santa I’d seen back at RFK Stadium, but it was definitely him—Jerry Garcia.

In the mid-’70s, Garcia, mandolin virtuoso Dave Grisman, and fiddle legend Vassar Clements had come together to record that album. It’s still the top-selling bluegrass record of all time—crossing over fans of gospel, bluegrass, country, and Deadheads (as fans of the Grateful Dead are often known). Through my whole childhood, it had been sitting there on our bookshelf, just waiting for me to connect the dots.

Arcana Americana

Once I started connecting them, those dots crisscrossed America from Nova Scotia to Appalachia to California to Africa before popping back up in the strangest of places—like full moon “polyethnic cajun slamgrass” tribal stomps in the mountains of Colorado and flashy headliners’ sets at Coachella.

But no matter where those dots led—tracing the catalog of the Grateful Dead, the coffeehouse folk of Bob Dylan, or the blues- infused revival of the British rock invasion—they kept coming back to a mild-mannered guy named Alan Lomax.

Lomax was a music geek who’d grown up in the early 1900s in Austin, Texas, and bounced between Harvard and other schools before finding his vocation. He started out by helping his father, a folklorist, gather field recordings of cowboy tunes. But Alan really came into his own when he took over leadership of the Library of Congress’s Archive of Folk Song in 1937.

He lugged clunky metal-and-wax recording equipment along with him all across the country. Lomax made over ten thousand field recordings and captured the voices and sounds of an America that most people never knew existed. He became fascinated by “the seemingly incoherent diversity of American folk song as an expression of its democratic, inter-racial, international character.”

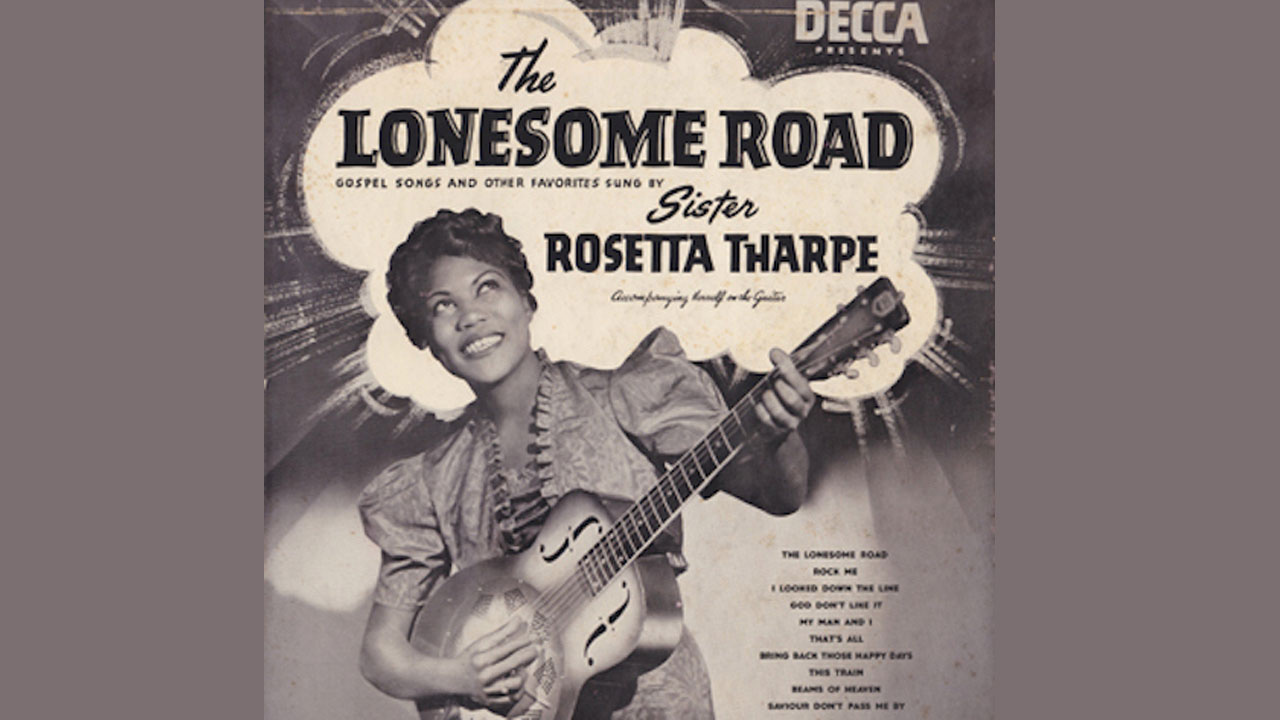

He interviewed the famous folk singer Woody Guthrie, jazz and blues legends Big Bill Broonzy, Jelly Roll Morton, Chicago guitar icon Muddy Waters, and dozens of others.

While a meaningful number of Lomax’s recordings captured the folkways of the African American South, the music of this country really emerged as a mishmash of traditions and influences. From the Scots-Irish Celtic tunes of hardscrabble Appalachia that grew into bluegrass and country music, to the French Catholic fiddle strains of Acadian music that then became the Cajun zydeco of Mardi Gras.

Everywhere displaced people suffered and prevailed, these redemption songs became a way of giving point and purpose to their struggle.

NOLA Legends Preservation Hall Jazz Band

“Homo Americanus is part Yankee ingenuity, part backwoodsman/ Indian or gamecock of the wilderness, and part Negro,” Albert Murray, the founder of Jazz at Lincoln Center, said of the country’s essential character.

“The blues tradition itself,” he wrote in The Hero and the Blues, “. . . is the candid acknowledgment and sober acceptance of adversity as an inescapable condition of human existence—and, perhaps in consequence an affirmative disposition toward all obstacles . . . whether political or metaphysical.”

When 1920s bluesman Furry Lewis lamented “I been down so goddamn long ’cause it seem like up to me,” he was embodying Murray’s “affirmative disposition” toward the obstacles of life. Naming it, claiming it, transcending it. Apparently his sentiment struck a chord—everyone from Nancy Sinatra to the Doors to the hip-hop superstar Drake have covered his song.

(#kendrickftw)

Murray’s protégé Stanley Crouch gave a name to this balance of adversity and triumph—swing. “It’s that combination of grace and intensity we know as swing. In jazz, sorrow rhythmically transforms itself into joy, which is perhaps the point of the music: joy earned or arrived at through performance, through creation” [emphasis added].

And that’s the thing that we’re really trying to tease apart here: that somehow, buried in this polyglot mishmash tradition of the American songbook, lies something potentially profound.

A philosophy, a way of being, a secret scripture—an arcanum—that not only sheds light on where we’ve come from but hints at a way forward for all of us.

Because these redemption songs aren’t just about looking on the bright side of lousy situations.

They’re powerful calls to radical transformation.

“The question’s not having hope,” Cornel West insisted at a lecture at Harvard Divinity School, “the question is being a hope. Having hope is still too detached, too spectatorial. You got to be a participant. You gotta be an agent. ‘You keep on pushing,’ Curtis Mayfield says. ‘Be a force for good,’ Coltrane says. ‘Mississippi god damn!’ says Nina Simone. That ain’t having hope. That’s being a hope. Courageously bearing witness regardless of what the circumstances are because you’re choosing to be a kind of person of integrity to the best of your ability before the worms get your body. Boom! that’s it. That’s blues. Beautiful tradition.”

Nina Simone

Courageously bearing witness before the worms get your body—and singing about it—is a uniquely American path to salvation. It’s transformative to name the pain rather than minimize it. But to take it from broken lament into triumphal celebration? That’s alchemy.

“Spiritual rebirth in the American Religion . . . is far closer to the patterns of Hermeticism than to doctrinal European Christianity,” Yale historian Harold Bloom writes in Omens of the Millennium.

Bloom’s saying that American spirituality has always been more subversive, more mystical, and more experiential than either the Protestant or Catholic churches of Europe would have allowed. Drawing from the same impulse that prompted Quakers, Shakers, Puritans, Mormons, Adventists, and dozens of other sects to flee persecution and seek their own Promised Land in America—American spirituality is wilder, weirder, and ultimately more subversive than many of the traditions it sprang from.

Temple Burn, Black Rock City, NV

“The American mode of self-knowledge is essentially Hermetic not Christian,” Bloom explains. “Initiation in American spiritual rebirth commences a process in which we become ‘healed original and pure’ Anthropos. Rebirth is emphatically not a repetition of physical birth, but a bursting into a new plane of existence previously unattained.”

It’s this death/rebirth sacred mystical initiation—this move from suffering to salvation, from mortal human to twice-born “Anthropos” that is so central to the American experience. It’s what Joseph Campbell was getting at when he connected the rock concerts of the Grateful Dead to the Dionysian rituals of ancient Greece.

As Zora Neale Hurston once said, “You’ve gotta go there to know there!” This is the secret scripture, the alchemical instruction manual, hiding in plain sight in the American song tradition.

Hermetically sealed.

Secretive.

But accessible if you have the key (often little more than a record album or concert ticket). Think of it as the Arcana Americana. We don’t need to pen new verses or gin up new stories to guide our way forward. They’ve been with us all along.

Bloom’s assertion, that scratch the surface of American Christianity and you’ll find a magical mystical body of initiatory knowledge, isn’t widely shared. That’s in large part because religion in America is either embraced by true believers who take it entirely at face value or dismissed by nonbelievers who deny there’s anything there to notice.

“Gnosis [or direct experience of reality],” Bloom asserts, “has been domesticated in America for two centuries now, so we have the paradox of a Gnostic Nation that does not know it knows! ” [emphasis added].

A Gnostic nation that does not know it knows! We have literally forgotten the tools we forged to help ourselves remember. A bitter irony, but also a chance to redeem it.

***

In 1996, the famous Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami premiered his film Through the Olive Trees at Lincoln Center in New York City. At the Q&A afterward an audience member asked why he had scored a film that was set in a remote village in northern Iran with classical music. Kiarostami responded, “Classical music has long ceased to belong to the West. It belongs to the world now.”

The same can be said of gospel, blues, jazz, and folk music—the Arcana Americana.

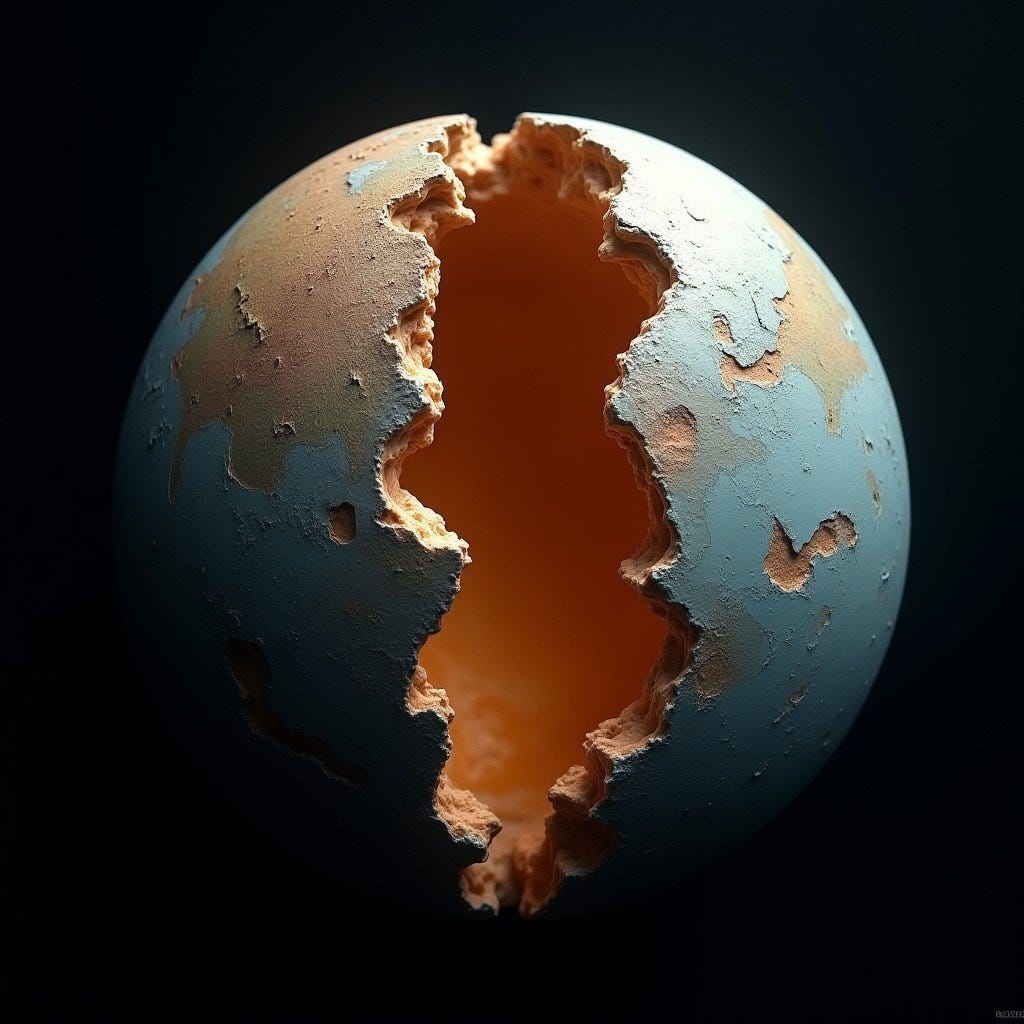

These redemption songs were forged in the fires of our collective hope and despair. Slavery, wars, exiles, homecomings. Racism. Intermarriage. Multiculturalism. Nationalism. The African Diaspora. European reformations. Chinese railroad workers. Japanese internment camps. Vietnamese boat people. The Irish potato famine. Trails of Tears, Ghost Dances, and reservations.

The Sound of the Men, Working on the Chain Ga-ang

Revivals and Awakenings—great and small. Marches. Protests. Assassinations. Tragedy. Triumph. Tribulation.

Transformation.

The Arcana Americana, perhaps even more than classical music, doesn’t belong to any country anymore. It belongs to the world now—an expression, forged in the fires of suffering and survival— that speaks to a deep and universal experience.

Of being knocked down again and again, but each time, rising up singing. A soundtrack for the Infinite Game.

When Alan Lomax looked back over his more than ten thousand recordings archived in the Library of Congress, he marveled at “the seemingly incoherent diversity of American folksong as an expression of its democratic, interracial, international character, as a function of its . . . turbulent many-sided development.”

Picking ourselves up, and doing it all again.

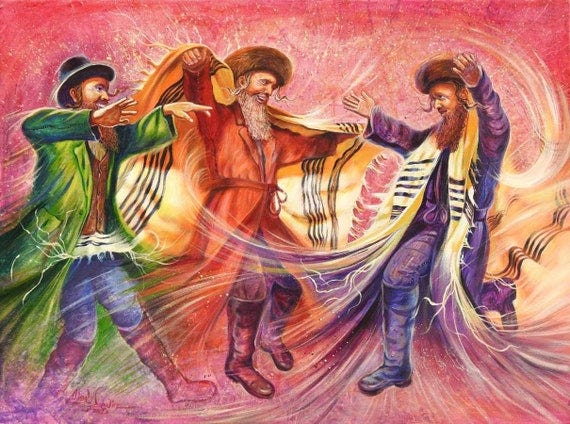

Dancing to forget.

Singing to remember.

While much of this tradition is steeped in the idiom of the Judeo-Christian tradition, as Harold Bloom reminds us, there’s a secret hidden within that secret too.

The Arcana Americana is a living hermetical and heretical tradition. It rejects the doctrine of Original Sin—that we are forever cast out East of Eden to suffer and atone.

In the place of guilty prostration, the Arcana Americana defiantly claims a second act, a transfiguration based upon the innate perfectibility of humankind.

Anthropos, Bloom calls it. HomeGrown Humans, if we prefer something more accessible.

As we try to mend our crisis in meaning, and the fractures that threaten to tear us apart, our redemption songs can bring us together.

Giving us hope, being a hope.

Shining the way, in our hymnals and our hoedowns.

![Review] Old & In The Way (1975) - Progrography Review] Old & In The Way (1975) - Progrography](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!_kF2!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F15733d70-07fb-4b4b-b5ba-e6e998fff802_600x597.jpeg)

Sometimes I get lost looking for hope. This is a great reminder that there is a long history of hope that is right in front of us for the picking. Yeah baby! Let’s sing and dance our way there (together)….And don’t let the bastards get ya down!

Grazie amico! Loved this one🙏🏼