Seems like a bunch of folks are writing navel-gazing posts about “Why I’m not going to Burning Man this year.” As if any of us give two hoots about their late summer travel plans!

This is not that.

But it is a piece I wrote a few years back as an introduction to a photography collection of art from the event. In writing it, I tried to take a fresh cut describing the event and how we all use it as a Rorschach Test for our own preferences and biases on culture, elitism, sexuality, substances, art, community and ecology.

FWIW, my sense is that the “first city” –the socially defined one you hear about on social media–has ballooned to obscene proportions, and is at risk of eclipsing the more ephemeral (and precious) “third city”–the mystic initiatory experience that it sometimes delivers.

That doesn’t mean there’s still not plenty of magic if you know where to go looking. But it does mean that the odds of having an ego-less transcendent experience go down considerably when you’re trapped in an echo chamber of digital narcissism.

Jonathan Haidt wasn’t wrong when he pegged the beginning of our smartphone malaise to around 2014. It took a few more years for portable cell towers and Starlinks to infiltrate the playa. But at this point, influencers go to the event, not to lose themselves in gobsmacked awe in front of giant art installations, but to pout and preen with those same art projects as backdrops to their own self-promotion.

Figure and ground have swapped entirely. And that’s a tectonic shift that may not be reversible anytime soon.

So whether you’re an initiate in that particular dusty Mysto yourself and want to drop into warm reflection, or a cynic looking for fodder for snarky tweets, read on…

The Way that can be named,” Lao Tzu once said, “is not the true Way.”

And that goes triple for Burning Man.

Attempts to describe what goes on at this annual gathering in the middle of the Nevada desert range from the overtly earnest “Ten Ways Burning Man Changed My Life (And Can Save the World)” to the reflexively judgmental “Burning Man is a pagan sex carnival for billionaires and an environmental catastrophe.”

As tantalizing as those tropes are, they miss the point entirely.

That’s because there isn’t a singular event to speak of, either critically or adoringly. Instead, there are at least three different Burning Mans, all getting crashed, smashed and lumped together in the conversation. And it’s not until you tease them apart to find the final one that things get really interesting. That’s arguably what all the fuss is about — a glimpse of “the Burn that cannot be named.”

The True One. Whatever that means at this late date.

Let’s untangle them one at a time.

The first version of Burning Man is the one that lives in popular imagination, caught somewhere between tales of “naked hippies in the desert” excess and breathless “supermodels, DJs and tech titans” star-spotting. Folks who don’t go, but like to fancy themselves In the Know, nod and cluck. They’ve watched the videos and scrolled through friends’ newsfeeds. Like Ibiza, or Studio 54 before it, it’s important, they think, to be familiar with this scene, but dangerous to commit to it. Work. Family. Skeptical spouses. Reputations. They doubt their ability to taste that much and not binge on the excess of it all.

The second version of Burning Man is the actual physical place. That only reveals itself if you do commit. Clear the calendar. Find the ticket. Pack your bags and beg for forgiveness in advance. Drive in along washboard roads reading the strange quotes staked along the fenceline. Bang the giant metal gong at the front gate if you’re a first-timer. Get persuaded, against your better judgment, to make a snow angel in the dust. Pull into the crowded city and search for a place to park and camp.

Black Rock City looks nothing like you’d imagined — like the extras from the last Mad Max movie threw a tailgate party and never left. Honestly, it’s a bit anticlimactic after all the hype. RVs, generators, shade tarps and Porta Potties radiate out in all directions. An elective refugee camp from 21st Century Normal. You wonder why everyone’s ambling around in their underpants and platform boots. The loucheness of it all feels slightly scandalous, and it’s only 10 in the morning.

But then, after a day of lying low, and trying to establish the basics of surviving on this inhospitable salt flat, the sun begins to set. The light in the sky shifts from washed out blue to tangerines, pinks and purples. The peaks to the east and west glow like the mountains of Mars. The mood around camp changes too, to one of quiet focus and preparation.

As the air cools, strange creatures come out from hiding. Fishnets and feathers. Hot pants and sequins. Furs and thigh-highs. Bedouin princes. Biker chics. Space pirates. Acrobats and conjurers.

Night falls and a procession to the open desert begins.

Walking is much too slow, so you hop on a bike and pedal towards the sounds and lights. Towards the disorientingly flat white expanse known as “the playa.”

Towards the giant wooden Man looming at the center of it all.

After the hot, cramped bedlam of the city, you suddenly burst out into the open. It’s freeing to see clear to the horizon again. The sensory overload of it all overwhelms. LED-lit mutant vehicles, ranging from giant schooners to scaly dragons to angler fish, glide by. Some bump otherwordly music, others are ghostly silent.

Scattered in between, rare fixed points in a hyperkinetic landscape, stand the art installations. Not regular, pretentious artist’s-statement-art. But knock-your-socks-off-draw-you-in-and-make-you-dance-art. Massive skeleton sculptures, kaleidoscopes and merry-go-rounds. Glow in the dark hopscotch, a phone booth to talk to God (she’s on the other end of the line, 24/7), a scale replica of a Gothic church propped up at one end with a stick. A spooky apothecary cheerfully advertising “we buy organic spare parts.”

Way back in 1966, John Lennon met Yoko Ono for the first time at a gallery in London. There was a rickety ladder that led up to a black canvas mounted near the ceiling, with a little spyglass attached to a chain. Lennon, not knowing what to expect, climbed the ladder, looked through the spyglass, and saw in Ono’s tiny, meticulous lettering the word “Yes!” That was the moment, he later admitted, that he fell head over heels in love.

The art of Burning Man does that too. It forces you up ladders and out onto limbs. It disturbs and disrupts and delights. It knocks you off balance. It sends you head over heels in love. It enraptures you with “Yes!” again and again.

At some point, all of this deranged creativity unmoors you. The music, the costumes, the mutant vehicles, the performances, the kindness (and strangeness) of strangers. You fall through every preconception, through every layer of culture and conditioning, into a space between worlds.

The corner of Everywhen and Neverwas.

And that, friends and neighbors, is where the third version of Burning Man shows up. When you’re too worn down, cracked open or gobsmacked to steer anymore. It doesn’t appear on any schedule (but around midnight and sunrise are good times to go looking), though when it does, it’s the experience that makes all the hassle and heartache worthwhile. It puts a shine in the eyes of those who have glimpsed it, and a glaze over the eyes of those who haven’t.

As Zora Neale Hurston once said, “You’ve got to go there, to know there.”

It’s a modern day rite of Eleusis. The Secret within the secret. The closest we can get to the Mystery in a world all but robbed of it.

Because this third version of Burning Man, the one that redeems all of the excesses and shortcomings of the whole ridiculous scene, is less an idea, or a location, than it is an initiation.

An initiation into remembering who we are. Remembering where we’re from. Remembering what we’re here to do. It’s what the Greeks called anamnesis — “the forgetting of the forgetting.”

If that sounds a bit much, don’t think all that Gnowledge comes cheap. It’s not any easier out there, in that biblical windswept desert than it is in our quiet, desperate lives at home. In fact, it’s a good bit harder. And faster too. Out there, the event horizon approaches zero. Causeandeffect collapse together. Think it (wrongly or rightly) and it is so. Resist and it becomes Resistance. But surrender, and it floats you Home.

That is what this third version of Burning Man offers, a chance to experience the tragic and the magic of the human condition in real time. Grace, to be sure. But a fierce grace that, as T.S. Eliot once said, “costs not less than everything.”

*****

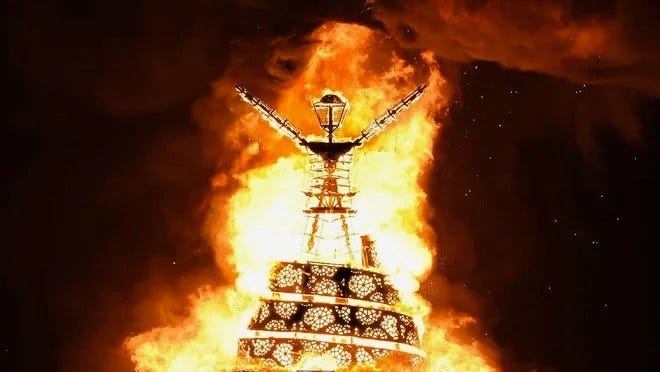

Then, on the night the Man burns, everything changes.

We’ve spent the whole week admiring him as we pedal past, guided by his light. But on the night he is to die, we grow impatient — with him and with ourselves.

The gathering horde circles around him, tens of thousands strong. The flames lick his thighs as he slowly raises up his arms in supplication. We thirst for his destruction. You can practically hear the cries of “bring us Barabbas!”

He dies so well, it almost makes you want to live a little better.

He is the sacrificial king — Osiris, Dionysus, John Barleycorn and the Nazarene — rolled into one. “Mankind,” Goethe observed, “has always crucified and burned.” Our Man is just the latest variation on that ancient theme.

Even all this is, perhaps, to say too much. No one should ever tell you what the Man means. That would only spoil it (and make all three of us wrong).

He is some things to all people, and All Things to some: a stand-in, an inkblot, a scarecrow on fire.

Our future. Our past.

And a truth-telling liar.

Just because no one can ever tell you what the Man really means, doesn’t mean you can’t find out for yourself.

So go looking, around midnight, or as the sun comes up. All alone, or with a friend. But be sure to look beyond the first and second versions of this gathering — all surfaces and sensations, places and people — and into the third version. The one that isn’t confined by a date on a calendar or defined by a pin in the map.

The one that cannot be named. The true one. The one we all, deep down, remember.

An edited version of this essay appears as the foreword in Phillip Volkers’ Burning Man book Dust to Dawn, Kehrer Verlag 2018.

Can’t make it this year, definitely feeling it. Always appreciate of Jamie’s perspective.

Listening to him speak there last year was definitely a high light.

Resonating deeply with this one.

Bought an old diesel short-bus on Craig's List in the early aughts, headed to BRC and never wanted to leave... until cell reception became a thing out there. Call me crusty, but that single pivot point really affected a lot of the magic for me as the years rolled on. Your writing is a wonderful reminder of the ineffable beauty, wonder, and spontaneous, generous CRAZY FUN that is Burning Man. Thank you, Jamie.